The Three Loves of Robert Troup

Robert Troup is often forgotten in stories of the United States’s founding, and it is not hard to see why. Though many of things Troup did ended up being important in the evolution of American politics, Troup was driven by a desire to be practical, and he was perfectly happy to do his work in small, well thought-out steps. He never sought glory for himself, and was willing to be a follower. But if Troup was looking for a relatively calm life, he chose the wrong people to spend it with. During his teen-aged years in New Jersey Troup managed to befriend both Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton, unwittingly committing himself to a turbulent friendship, a stormy love affair, and being caught in the middle of one of history’s most famous duels.

College Years and Hamilton

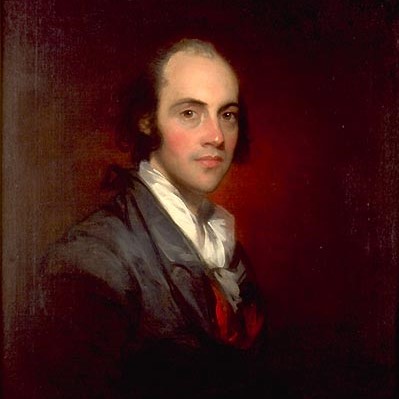

Robert Troup was born in New Jersey in August of 1757, the son of a privateer. Troup’s parents both died when he was still quite young, and he ended up being raised by his older siblings.¹ Not much is known about his early life; clear documentation of his existence starts around the time he met Alexander Hamilton. Troup likely met Hamilton when Hamilton was attending school in Elizabethtown, New Jersey, as Hamilton prepared himself for college. Eventually the young men found themselves roommates at King’s College, and it was during that time that they formed a friendship that would last the rest of their lives. The two had a lot in common, both being orphans trying to get ahead with very little money. Their approaches to life were often rather different, however. While Hamilton paid little attention to his personal finances, Troup was often worrying about money.² Their differing views on money highlight what is perhaps the most important difference between the two men: while Hamilton considered a moment wasted if it was not filled with grandeur, Troup was nothing if not practical. Though this difference sometimes caused friction between them, it would ultimately be one of the components that made them so successful when they worked together in politics.

In my original article on Alexander Hamilton, I argued there was much evidence from the early years of their acquaintance to suggest that Troup and Hamilton became lovers; now I am not sure. It is true that Troup continued to live with Hamilton for a year after his graduation.³ Certainly that would make sense if they had become romantically attached, but they were also both orphans, trying to get their education and start a viable career before the money they had been loaned by their friends and relatives ran out. Troup continuing to live with Hamilton may have made economic sense. Living together briefly would also not be entirely strange for friends. Thus, that piece of evidence does not seem very strong. It is also true that Hamilton gave Troup a collection of poems he had written, which according to biographer Ron Chernow, “the latter [Troup] proceeded to lose during the Revolution.”⁴ In my article on Hamilton I used this too as evidence of a romantic and/or sexual relationship between Hamilton and Troup; but if the poems were romantic in nature, and Troup did indeed destroy them so no one else would ever see them, why did Troup leave behind a record of their existence at all?

That being said, while I no longer believe there is enough evidence to say that Troup and Hamilton had a sexual and/or romantic relationship, it is still entirely possible, as will be shown later, that Troup was LGBT+. If this is true, shared experiences as LGBT+ men may be part of what fueled Hamilton and Troup’s friendship.

The War and Aaron Burr

Troup eventually parted ways with Hamilton to continue his law career, and he became a clerk for John Jay. This did not last long however before Troup decided to join the army, which he did in May of 1776. Troup was almost twenty at the time. Troup had a fairly distinguished military career, and was taken as a prisoner of war in the Battle of Long Island. After a long stint in a prison ship, Troup was returned to the Continental Army, and he became an aide de camp to General Horatio Gates.

Troup left the army sometime around 1780, and decided to resume his law career.⁵ He made plans to study law with another friend from Elizabethtown, Aaron Burr. Troup wrote to Burr from Princeton, New Jersey, and asked him to come and take him away. At the end of this letter, Troup proclaimed to Burr: “If we once get together I hope we shall not soon be parted. It would afford me the greatest satisfaction to live with you during life.”⁶ Burr could not immediately rush to Troup’s aide, and in the meantime Troup continued to write to Burr about their future plans, at one point telling him, “It is true, Mr. Stockton [the man they planned to study under] has unmarried daughters, and there is [sic] a number of genteel families in and around Princeton. But why should we connect ourselves with any of them, so as to interrupt our studies?”⁷ In all of his letters to Burr at this time Troup dreamed of them being reunited, and finding somewhere they could live peacefully, just the two of them. Burr’s delay lasted longer and longer, and Troup began to get angry. Burr tried to reassure him; he would come for Troup, and in the meantime, Troup must “Hold yourself aloof from all engagements, even of the heart.”⁸ [emphasis original]

Whether the relationship between Burr and Troup was romantic and/or sexual is uncertain. Burr was very likely bisexual; he mentions flirting with men in his diary, and he had an affectionate relationship with Jeremy Bentham, a British writer who is one the few one-hundred percent confirmed gay men of the era.⁹ Of course the fact that Burr was bisexual does not prove Troup had a relationship with him, but it gives us more solid ground to work on than if the sexual and romantic orientions of both men were unknown. One must then look at the actual evidence from Troup and Burr’s interactions. Troup’s desire to live with Burr while studying the law does sound like they are in a romantic relationship. In addition to telling him that it would give him “the greatest satisfaction” to live with Burr, Troup at one point wrote that “My future prosperity in life depends in a [sic] great degree Burr you may imagine on my living and studying with you and the sooner we [find lodging?] in some retired place where we can live cheaply and without interruption, the better.”¹⁰ From these quotes it sounds more like the most important part of Troup’s future plans was being with Burr, with studying the law being a secondary goal. Then one must consider Troup’s intriguing comment that once they were living together they should ignore any potentially interesting women. This was made as a somewhat light hearted joke, but is that not exactly the way a hopeful lover would ask someone to be exclusive to them? And then, as Burr failed to come get Troup and Troup began to grow angry, Burr reassured him by making clear that he too thinks they should each forsake other potential romantic partners. These clues may not be definitive, but they certainly paint an interesting picture.

Burr finally did make good on his promise. Troup and Burr moved to Albany in November, 1781.¹¹ Whether this time together fulfilled all of Troup’s dreams is unknown, but it did not last long. On July 2nd, 1782, Burr married Theodosia Prevost.¹² Burr and Troup had met Prevost during the war; though she was at that time married to a British officer, her husband was initially stationed in the Carribean, so she was able to become a center of social life for Loyalists and Patriot alike.¹³ As I said in my article on Burr, Troup and Burr were part of a circle of young men who hung around Prevost. Though all of these men admired her, it seems none were aware when she began having an affair with Burr. Indeed, Troup’s letters from the time suggest that he thought him and Burr were both merely friends with the vivacious socialite. Therefore, the end of their time together may have come as a shock to Troup, though it is impossible with currently available evidence to say for sure.

Politics, Goelet, and Burr as an Enemy

With Burr married and beginning his law career, Troup turned once again to Hamilton, who was also living in Albany. Hamilton was by this point also married, and Troup came to live with Hamilton at Hamilton’s in-law’s home, Schuyler Manor. Troup lived there for a few months until finally taking and passing the New York Bar Exam, and beginning his legal career. He then moved back to New York City, the British Army having just left. Several years passed as Troup built up his law career, and in 1787 Troup married Janet Goelet. The two would be married until Troup’s death in 1834, and would have six children, four of whom survived infancy.¹⁴

Very little is known about Troup’s relationship with Goelet. I could not find any of his correspondence with her, and the only letter I uncovered in which he mentions her is one in which he tells Hamilton: “Thank God I am happy to an extreme in my wife & children & have as little reason as any of my neighbours to complain of business.”¹⁵ Of course a gay man of that time period would have felt compelled to lie, but with no evidence contradicting his statement we are forced, for the moment anyway, to take him at his word, and assume that he did love Goelet. This being the case, I will not hypothesize Troup to be homosexual, though this by no means proves he was straight.

1787 was also the year of the Constitutional Convention. Since 1781, the country had been living under the Articles of Confederation, but the framework created by the Articles proved unstable and unusable. With the creation of the new Constitution, a new era of American politics was born. The next decade would see a sharp division as Americans became either Federalist, proponents of big government and industrialization, or Democratic-Republicans, proponents of small government and an agriculture-based economy.

Troup was not just a Federalist. Side by side with his friend Hamilton, Troup helped found the Federalist party, and while Hamilton created enduring political philosophies and waged grand battles for the character of the United States, the pragmatic Troup quietly invented modern party politics. Troup worked on the ground level, hand picking Federalist candidates and overseeing their election. He kept himself apprised of all political movements in New York, the Federalist stronghold, and made sure party members were doing what he -or Hamilton- wanted them to.

It was in his role as a Federalist party organizer that Troup found himself face-to-face with Aaron Burr. Burr was caught in the clash between Hamilton’s Federalists and Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans, and he seemed to like it that way. As many people of the time saw it, Burr was willing to switch sides whenever it suited him. This infuriated many, and it may have been what cost him Troup’s trust. In 1780 Burr may have been all Troup needed to be happy, but by 1792 Troup was telling his old mentor Jay: “The quibbles & chicanery he made use of are characteristic of the man.” Troup was talking about a controversial case in which members of the opposition party had claimed that a Federalist victory was illegitimate; they wanted mishandled votes thrown out. Burr gave an opinion in the case, and Troup told Jay, “We all consider Burr’s opinion as such a shameful prostitution of his talents—and as so decisive a proof of the real infamy of his character, that we are determined to rip him up— We have long been wishing to see him upon paper, & we are now gratified with the most favorable [exi?]bition he could have made.”¹⁶

Is it possible, however, that Burr had already lost Troup’s trust? As I mentioned before, Troup does not seem to have known that Burr had become Theodosia Prevost’s lover until Burr and Prevost’s relationship became common knowledge. By that point, Burr had been having an affair with her for some time. If Burr fell in love with someone else and cheated on Troup, this may explain why years later Troup, usually so loyal and devoted to his friends, was so ready to destroy Burr.

The next decade saw the Federalist party achieve unimaginable victories and suffer bewildering setbacks. Most of these setbacks were due to the party’s founder, Hamilton. In 1797, Hamilton put himself in the middle of the first political sex-scandal in United States history. The Reynolds Affair was shocking, ugly, and nearly ruined Hamilton’s marriage. Still, the Reynolds Affair was not his undoing, nor was it the Party’s, and it is often blown out of proportion in terms of its role in the destruction of either. Far more destructive was an open letter Hamilton wrote not long after. Hamilton wrote a letter, intended to be circulated among his closest political confidants, explaining why Federalist John Adams must not be reelected president. Hamilton was not shy about explaining in astounding detail just why he hated Adams. When the letter was leaked to the public, it proved an enormous humiliation to Hamilton and to the Federalist party, and led to divisions within the party. Troup said it proved Hamilton was “radically deficient in discretion.”¹⁷ Though experts then and now have debated whether Hamilton’s letter cost Adams the election, he did lose, and so began the end of the Federalists.

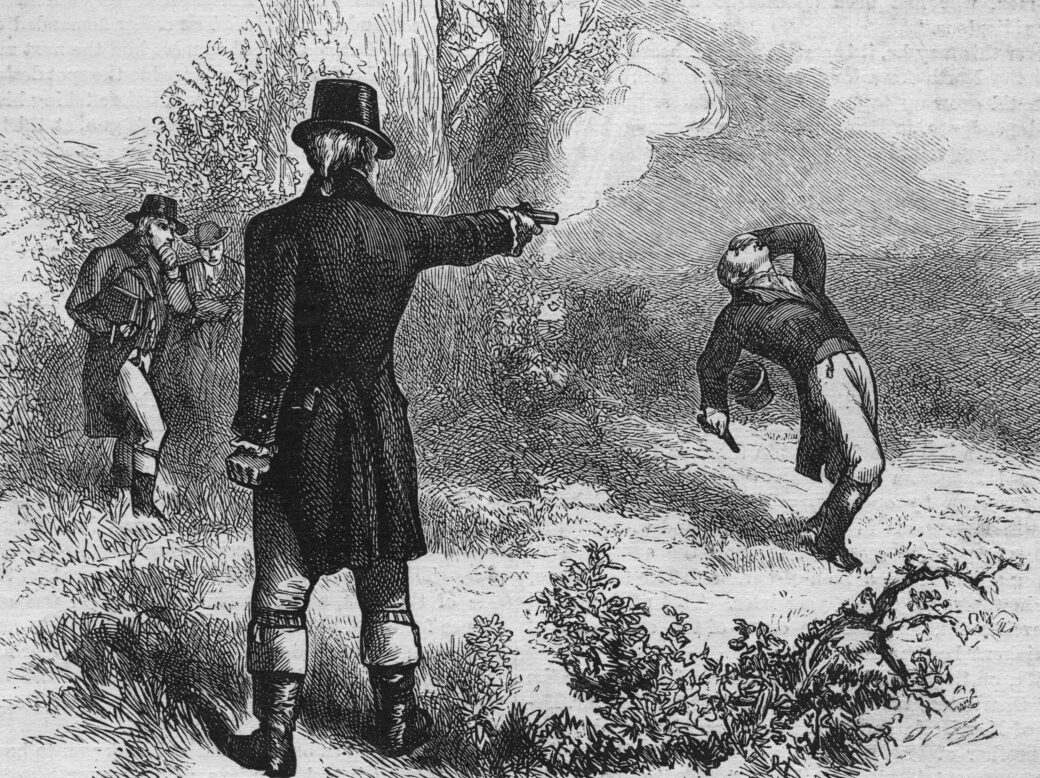

There is little evidence to say whether Hamilton’s catastrophic indiscretions hurt his relationship with Troup. They seemed to remain friends, and on July 10th of 1804, Hamilton visited the sickbed of a deathly ill Troup. Hamilton remained there “more than half an hour,” according to Troup, and spent the whole time giving endearing, if unsolicited, medical advice. Troup spent the next few days drifting groggily in and out of consciousness.¹⁸ While he slept, Troup’s world imploded in such a spectacularly tragic way that it is hard to think of another person in history who suffered so uniquely.

The Duel

When Troup awoke a few days after Hamilton’s visit, it was to find his best friend dead, at the hands of none other than Aaron Burr. Troup’s reaction to this event is not recorded, though he did have a hand in planning and paying for Hamilton’s funeral, and in financially assisting Hamilton’s now desperate family.¹⁹ Burr headed calmly to the nation’s capital, to perform his final duties as vice president. Burr would not return to New York until 1812, and filled the interim time with his own trial for treason, a tour of Europe, and a string of love affairs. When Burr did return, it was to find himself rather unpopular. Even those who had often wished Hamilton gone hated Burr for killing him, and there was no chance of Burr rebuilding his political career. Instead Burr decided to try to pull together the remains of his law practice, and he turned for assistance to Robert Troup.²⁰ What Troup must have felt in that moment is unimaginable. Burr had been Troup’s friend in his youth, possibly his lover in the early days of their adulthood, and then his enemy at the height of their careers, only to have all these considerations blown away when Burr murdered a man to whom Troup was devoted. After considering all of this, Troup lent Burr his law library. With the rest of the country uniting in condemnation of Burr, this gesture could only be seen as an act of forgiveness.

If you value what I do here, please consider becoming my Patron! 18th Century Pride is creating LGBT+ History Content | Patreon

- “Robert Troup”, Stefan Bielinski, Robert Troup (nysed.gov)

- Alexander Hamilton, Ron Chernow, 53

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 70

- See #1

- Robert Troup to Aaron Burr, 27 April, 1780, 44806674.pdf (americanantiquarian.org)

- Robert Troup to Aaron Burr, 16 January, 1780

- Aaron Burr to Robert Troup, 15 May, 1780

- See my article “Burr’s Missing Puzzle Piece”

- Robert Troup to Aaron Burr, 16 May, 1780

- See #1

- “The Courtship of Theodosia Bartow Prevost and Aaron Burr”, Aya Katz, The Courtship of Theodosia Bartow Prevost and Aaron Burr | Historia Obscura

- See #9

- See #1

- Robert Troup to Alexander Hamilton, 15 June 1791, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-08-02-0407

- Robert Troup to John Jay, 10 June 1792, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jay/01-05-02-0225

- Chernow, 627

- Ibid., 697

- Chernow

- Ibid., 722

pupbeepaws

Thank you for your insight and all your hard work!! I’ve taken an interest lately in Robert Troup because of his probably romantic relationship with Hamilton, but haven’t read anything about him yet. This is where I start! Now I’m reeling from his complicated relationship with Burr! It sounds like Burr really strung him along, and then wasn’t what Troup wanted once they finally started living together. His shattered fantasy of a happy domestic life, awww. I want to look more into his interactions with Burr. It definitely sounds like he was pursuing a romantic relationship there, and I’m saddened to think it might have been once-sided. Admittedly I don’t know much about Burr, but I get this impression he’s kind of slimy, and that he uses people. I worry for Troup’s poor lovesick heart. I don’t think his affections were properly placed. But at the same time I’m so curious…why do people like Burr? Everything I read makes him sound so fake and shady, but he had so many friends and lovers. What’s his secret?? He must be charming until you get to know him. I still haven’t done any research on Burr. I’m saving him for later, lol.

Sorry for rambling. Thank you again for all the information!

megangack

I go back and fourth on whether or not Hamilton and Troup had a romantic relationship. Lately I’ve been leaning towards no, but I’m open to hearing arguments about it; it’s hard to tell with them.

As for Troup and Burr, what a story! I think it sounds like a romantic relationship; but then for Burr to display such disinterest in Troup later, and eventually marry Theodosia, their mutual friend…? Crazy. Poor Troup.

If Troup did try to have a committed, domestic relationship with Hamilton, and then Burr, Troup could be so important to LGBT+ historical work! In all eras queer people have had more than just one night stands, but it’s usually so hard to find evidence of this kind of non-traditional homemaking.

As for what you said about Burr, I think Burr must have been complex. He did do some good things, and I think he really did endear some people to him. But he could also quickly give up people or things if they no longer served his long term goals, and didn’t seem to feel a lot of remorse about it. To be fair, Alexander Hamilton did this too.

Thank you for your comment (I get so few real ones!) and for all of your support of my work! I’m so glad I can help you on your own research journeys!

Megan T

Interesting article! Troup actually wrote about the duel in a letter to Hamilton’s other friend Timothy Pickering when he was attempting to write his bio of Hamilton in the 1820s.

Here’s a reprint of the part of the letter talking about the duel (the first part seems to allude to a fear amongst Hamilton’s friends about a possible duel a while before the actual duel took place)

In the midst of their alarm ^ the imaginations of Hamilton’s law friends raised up the spectre of a duel between him and Burr; and to prevent a real one Hamilton’s law friends unanimously resolved on using all prudent means. For this purpose the first step they took was to request me to wait on Hamilton to ascertain the truth of the reports, and to inform him of our fears. I waiting on him accordingly: he laughed at our fears & declared that Burr was not in possession of any letter to Morris: that Burr knew the nature of the testimony he expected to give in the trial of the libel suit, and was satisfied with it: and that there was not the slightest ground for apprehending a duel.

I reported to our law friends the result of my conference with Hamilton: we were all exceedingly rejoiced: the trial of the libel suit did not take place: And thus we were unfortunately lulled into a false security

The duel originated afterwards from a different cause

When Hamilton accepted Burr’s

– – –

17

challenge a Court in which Hamilton had a good deal of business, was on the eve of sitting; and it was agreed that the duel should be postponed till after the court had finally adjourned; to the end that Hamilton might perform his engagements to his clients.

In the latter part of the afternoon, preceding the duel ^ Hamilton finished a lengthy law opinion, and soon afterwards he paid me a visit. I was then confined to the house, by a lingering disease, which, after his death, I discovered that he and some other friends, conceived would be mortal. During his visit he limited his conversation to inquiries into the state of my health, and to advice concerning the best mode of re-establishing it. His manner struck me as having an air of peculiar earnestness, and solicitude, but not dreaming of any duel, I attributed the manner solely to his sincere, and long standing, friendship for me.

King has more than once told me that while

– – –

18

the duel was pending, Hamilton made him repeated visits, in each of which the duel was the only subject of conversation. Notwithstanding Hamilton’s mind was fully capable of viewing the duel, in any possible light, yet King entered into solemn argument with him against it, under any circumstances whatsoever. Hamilton freely acknowledged that duelling could not be defended on any principles of reason, morality or religion; but at the same time, declared that he would not avoid meeting Burr. After King saw that Hamilton’s purpose was not to be changed, he suggested to him that Burr undoubtedly meant to kill him and consequently it was his duty to make such preparations for the contest as would place him, as nearly as could be done, on equal ground with Burr. To these suggestions Hamilton answered he could not endure the idea of taking the life of a human creature in private rencontre; to which King replied “Then Sir you will go like a lamb to be slaughtered”.

Mr Pendleton who

– – –

19

was Hamilton’s second, also told me that the day before the duel he, with difficulty, prevailed on Hamilton to take his pistols in hand that he might, in some degree, become familiar with the use of them. Pendleton thereupon delivered him one of the pistols. He quickly raised it to a level, but, dropping his arm as quickly, he returned the pistol to Pendleton; and this constituted the whole of his preparation to fight an antagonist very adroit in firing with pistols.

I verily believe that Hamilton had not fired a pistol since the termination of the revolutionary war.

There cannot be any doubts, from Pendleton’s statement of what passed at the duel, that Hamilton fired in the air.

How Hamilton commenced his preparation for the army, and how he acquired his knowledge of the practice of the law – for admission to the bar, I have heretofore related in memoranda sent to J.A. Hamilton. Altho’ I have not retained copies of those memoranda

– – –

20

yet if they should not be with you, or if they should be lost, I will endeavour to furnish you with the facts.

I have now completely exhausted my stock of recollections respecting a man whom I loved when we were boys together; and whose transcendent talents, public spirit, and private virtues, since his arrival at Manhood, I have never ceased to admire.

I rejoice that I have lived to contribute some portion of the materials for illustrating Hamilton’s name. I rejoice still more that it has happily fallen to your lot to be the instrument of transmitting his name, in all its native [?] lustre, to impartial posterity.