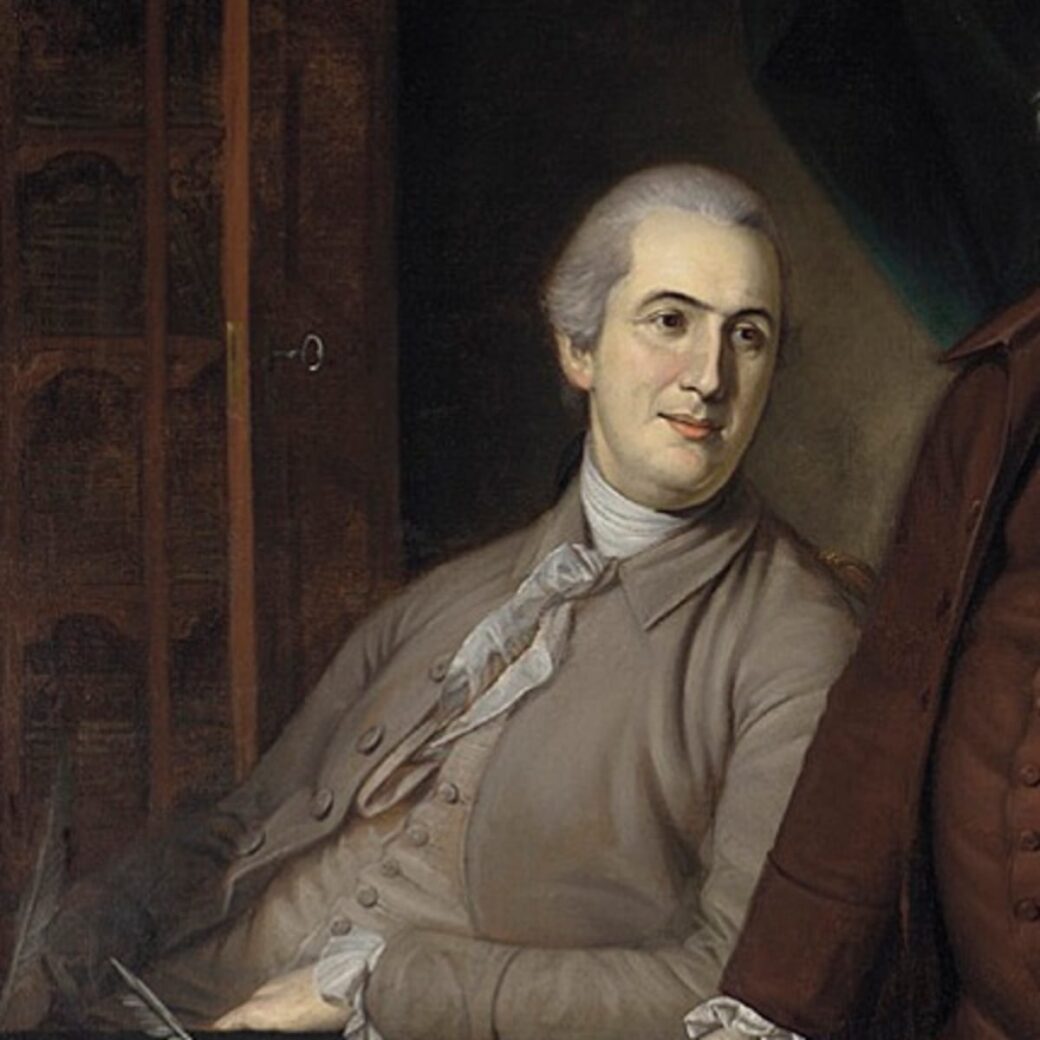

The Adventures of Gouverneur Morris

Whatever his flaws, Gouverneur Morris was his own person. Whether he was joining the Revolution even though it meant being ostrasized by family, marrying an infamous woman and losing friends, or just having sex with every pretty woman (single or married) in Paris, Morris did what he wanted. Morris was unashamed of who he was. But did being who he was include being bisexual? To find out we must dig through the remnants of a wild, tradition smashing life.

Who is Gouverneur Morris?

Gouverneur Morris was born on January 31st, 1752, the youngest son of a wealthy, aristocratic New York family. Morris entered King’s College (now Columbia University) at age twelve, and graduated at age sixteen. Morris’s plan was to become a lawyer, and he was admitted to the New York Bar in 1771. Though Morris was rather Conservative (by the standards of his day), when the Revolution broke out Morris decided his loyalties lay with the new government. His family chose to remain loyal to the British Empire. Morris became a delegate to the Continental Congress in 1778, where he served as assistant to Superintendent of Finance Robert Morris (no relation). He signed the Articles of Confederation, though he would also go on to be part of the Constitutional Convention, and he wrote the famous Preamble.

After the Revolution Morris went to France for business, and ended up being made United States’ ambassador to France. Morris served in this position for much of the French Revolution, until the new French government demanded his recall for opposing the Revolution. Morris then served as a senator. On Christmas Day of 1809, he married Anne Cary “Nancy” Randolph, the disgraced black sheep of an aristocratic family and Morris’s housekeeper. A few years later the couple had a son, Gouverneur Morris II. Morris died in 1816 from botched self-surgery.¹

Women

Morris was widely known during his lifetime for being a ladies’ man. When Morris lost his leg in a carriage accident in 1780, a rumor started that he had destroyed his leg by jumping from a woman’s second floor balcony to escape her furious husband.² Some of Morris’s wildest affairs happened while he was in France in the 1790s. While there he started an affair with Madame Flahaut, the wife of a nobleman. His diary is littered with notes that he went to see her to “do the needful,” or “celebrate,” two of Morris’s favorite euphisms for sex.³ This happens at a variety of locales, including Flahaut’s apartment in the Louvre while her husband is home and a convent. There’s even a hint that Morris may have gotten Flahaut pregnant.⁴

And Flahaut was by no means the only woman Morris was having an affair with at that time. In his diary Morris recounts beginning his intricate process of seduction with several other women, one of them Flahaut’s niece.⁵ Recounting a visit he paid to a Madame de Foucault, Morris records in his diary: “I tell her that I wish she loved me enough to let me give her a Child. She asks if I think myself able. I reply that at least I could do my best, and then as Monsieur is listening I change the Conversation.”⁶

In 1809, at the age of fifty-seven, Morris married Anne Cary “Nancy” Randolph. Randolph came from an extremely powerful and well respected family, but she herself lived in disgrace. Randolph was suspected of having given birth to her brother-in-law’s child, which it was suspected either Randolph or her brother-in-law then murdered.⁷ While many believed in Randolph’s innocence, this nasty rumor was often thrown back at her. She became Morris’s housekeeper a few years after her family disowned her. It is possible that at that point Morris was already interested in Randolph as more than a housekeeper. Eight months later, on Christmas Day, Morris and Randolph got married during what guests had been told was simply going to be a Christmas party. Their only child, Gouverneur Morris Jr., was born three years later. Though Morris must have enjoyed the shock his marriage caused, he seems to have been genuinely in love with Randolph. During one of the rare times he was away from his wife when their son was a baby, Morris wrote her and the baby a love poem, and according to Randolph: “After this was written Mr. Morris and myself were never absent from one another except one night.”⁸

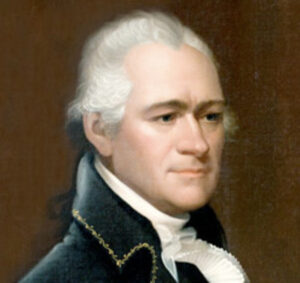

Hamilton

The male-male relationship most often looked at in Morris’s life is his friendship with Alexander Hamilton. Morris likely met Hamilton while the two men were living in New York before the war. When the war started, Gouverneur Morris found himself part of the Committee of Correspondence, a group within the state’s government tasked with keeping New York in contact with other parts of the Revolutionary effort, including the Continental Army. Morris began an official correspondence with Hamilton, then serving as aide de camp to George Washington, and Hamilton and Morris quickly came to enjoy conversing with one another.

After the war Hamilton and Morris became close friends and political allies. Reading these letters, I was struck by their playful tone. Hamilton and Morris were both sarcastic and witty, and communicating with each other unlocks a silly side not usually displayed so fully by either of them. In one letter, while telling Morris his thoughts on a bank created to compete with the Bank of the United States, Hamilton manages to turn his political commentary into a long joke about Morris’s sex life. Hamilton tells Morris: “Were I to advise upon this occasion, it would be as soon as possible to bring about a marriage or, perhaps what you will prefer, an intrigue [affair] between the old bank and the new. Let the latter be the wife or, still to pursue your propensity, the mistress of the former. As a mistress (or you’ll say a wife) it is to be expected she will every now and then be capricious and inconstant…”¹⁰ Their letters are full of jokes like this, even as they discuss serious matters.

Not only do they appear to have had a lot of fun together, Hamilton and Morris appear to have forged a strong bond. In one letter Hamilton confessed to Morris that “Every day proves to me more and more that this American world was not made for me.”¹¹ Referring to himself as a foreigner who did not belong in America was Hamilton’s favorite self-hate move whenever he was depressed. That he used it with Morris is interesting because it suggests Hamilton had discussed his origins with him, something Hamilton did with a very select group of people. This is reinforced by Morris’s diary entry from the day spent writing Hamilton’s eulogy years later, in which Morris noted: “The first point of his biography is that he was a stranger of illegitimate birth.”¹² Of course, Morris probably heard the rumors about Hamilton’s early years circulated by Hamilton’s enemies. Still, the facts that he believed it to be true, and that Hamilton freely alluded to it in letters to Morris, both suggest that they may have openly discussed it at some point. Considering Hamilton worked hard to distance himself from his past, this would show he had great respect for, and trust in, Gouverneur Morris.

As mentioned before, Morris wrote Hamilton’s eulogy. He was also by Hamilton’s side when he died. In his diary Morris recalls how he initially heard Hamilton had been killed instantly in the duel. When he learns the next day that Hamilton is still alive, he immediately goes to see him. Morris notes: “When I arrive he is speechless. The scene is too powerful for me, so that I am obliged to walk in the garden to take breath. After having composed myself, I return and sit by his side till he expires.”¹³ That Morris was there in Hamilton’s final moments, along with a small group of Hamilton’s closest friends and loved ones, is another mark of the important place he held in Hamilton’s heart.

But was Morris’s deep connection to Hamilton one of friendship, or was it romantic and/or sexual? Some of the letters include suspect passages. In one, Hamilton begins: “Today being sunday I have resolved to give an hour to friendship and to you. Good people would say that I had much better be paying my devotions to the great-” The next chunk of the original manuscript is missing. Apparently less of it was missing when Henry Cabot Lodge published Hamilton’s papers than is missing now, because he included a bit more of this section. After perhaps a few missing lines, Hamilton continues: “devotions I mean; for with so lively an imagination as yours it is necessary to be explicit, lest you should be for making a different association that would not suit me quite as well.”¹⁴ This jumble is a bit difficult to decipher. It sounds like probably Hamilton describes giving some/providing someone with something, and Hamilton is clarifying that he meant devotions, and not sex. This could be a raunchy joke between friends, particularly as it seems to involve religion and Hamilton and Morris were the last two men you would find in a church. That is, of course, not the only possible explanation. If “the great-” was going to be followed by a euphemism for God, then it is possible that the misinterpretation Hamilton alludes to had something to do with Hamilton doing something sexual for a man. In that case, could Hamilton’s comment that he would not want Morris to infer that be a playful way of reminding Morris that he was not going to seduce Hamilton?

In another letter, Hamilton made a comment that was perhaps more clearly flirtatious. In this letter Hamilton apologizes to Morris for not having written in a while, but tells him that he hopes Morris will forgive him “as I hope you believe there is no one for whom I have more inclination than yourself—I mean of the male kind.”¹⁵ This could be read two ways: Hamilton could be saying that there is no one he loves more than Morris -as a friend (within the heteronormativity of their society, there may be the assumption that if Hamilton loves Morris as much as he loves any man, he means he loves him in a platonic way). Or, Hamilton could mean that the only person he loves more is his wife. This second option definitely has flirtatious possibilities.

Morris’s letters to Hamilton are more typical of friends of the era, if rather sarcastic and playful. There is only one moment in Morris’s letters to Hamilton that really stands out. In 1800, Morris wrote a letter to Hamilton about the Convention of 1800. Midway through the letter, the original manuscript reads: “Finally this vention is unlimitted in it’s Duration. Such my dear is the Result of our french Negotiation which evidently ces us in a critical Situation.” The copy I read, on Founders Online, fills in the gaps using the copy of this letter in Morris’s letter book. With the gaps filled in, the sentence reads: “Finally this ⟨con⟩vention is unlimitted in it’s Duration. Such my dear ⟨Sir⟩ is the Result of our french Negotiation which evidently ⟨pla⟩ces us in a critical Situation.”¹⁶ The amending of “vention” to “convention” and “ces” to “places” is of little consequence, but the change form “such my dear” to “such my dear sir” is noteworthy. As I explained in my article on the correspondence between Alexander Hamilton and John Laurens, in the world of eighteenth century language there is a big difference between using “dear” as adjective and using it as a noun; the first one is a typical address for a friend, the second is a term of endearment. So which did Morris mean? Why would he say “my dear” in the letter he sent to Hamilton, but “my dear sir” in the copy he kept for himself? His omission of the word in the manuscript copy could have been an accident. On the other hand, perhaps he thought his letter book was more likely to fall prey to prying eyes than the letter, or perhaps he was just too afraid to repeat the confession of taboo affection in a second copy. For now this remains a puzzle, but if Morris really did intend to call Hamilton “my dear,” it would definitely suggest they were either having a relationship or had a romantic history.

That Gouverneur Morris loved women is clear. Prior to his marriage, Morris seemed to devote most of his free time to pursuing and having sex with beautiful women. He also seemed to genuinely love his wife, or at least genuinely have fun spending the last chunk of his life with her.

Whether Morris may have also loved men is unclear. His correspondence with Alexander Hamilton was definitely full of more humorous sarcasm and silly playfulness than one would normally see in correspondence between friends of that time. But is it right to assume that the relationship must have been something other than friendship, simply because it was unusually fun? There are a few passages where it seems like Hamilton may have been flirting with Morris. In particular, his comment that “there is no one for whom I have more inclination than yourself—I mean of the male kind,” is most easily explained as a flirtatious comment. This is just one comment, but since Hamilton actually was bisexual, he was probably cautious about what men he flirted with, even jokingly. Even if Hamilton and Morris were friends and not lovers, Hamilton’s willingness to make that sort of joke may hint that Hamilton knew Morris was not as horrified by such things as some people of their era. That being said, Morris never seems to have flirted with Hamilton via letter, except in that one case where he may merely have made an embarrassing typo. Morris and Hamilton’s relationship can not yet be labeled unequivocally as romantic and/or sexual, but it definitely merits further study.

Gouverneur Morris was never afraid to do what he wanted to do, or be who he wanted to be, no matter what society or even his own family said. We may not yet know for sure what Morris’s orientation was, but whatever the case, it is safe to say he was not ashamed of it.

- “Gouverneur Morris”, Britannica, Gouverneur Morris | American statesman | Britannica, “Gouverneur Morris”, GOUVERNEUR MORRIS (army.mil), and “Gouverneur Morris: Penman of the Constitution”, Gouverneur Morris: “Penman of the Constitution” (historythings.com)

- John Jay to Gouverneur Morris, 5 November 1780, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jay/01-02-02-0131

- For examples of this see: A Diary of the French Revolution, Gouverneur Morris, Read Books Ltd.. Kindle Edition, 1717, 1993, 2419

- Ibid., 1374

- Ibid., 2657

- Ibid., 2479

- “The Confessions of Gouverneur Morris”, The Confessions of Gouverneur Morris | The National Endowment for the Humanities (neh.gov)

- Gouverneur Morris: Author, Statesman, and Man of the World, James J. Kirschke, 264-265, Gouverneur Morris: Author, Statesman, and Man of the World – James J. Kirschke – Google Books

- .

- Alexander Hamilton to Gouverneur Morris, 21 February 1784, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-03-02-0331

- Alexander Hamilton to Gouverneur Morris, 29 February 1802, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-25-02-0297

- The Diary and Letters of Gouverneur Morris, Ann Cary Morris, 468-469, The Dairy And Letters Of Gouverneur Morris – Ii : Anne Cary Morris : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

- Ibid., 468

- Alexander Hamilton to Gouverneur Morris, 21 February 1784, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-03-02-0331

- Alexander Hamilton to Gouverneur Morris, 19 May 1788, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-04-02-0237

16. Gouverneur Morris to Alexander Hamilton, 19 December 1800, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-25-02-0137. For more information on what a letterbook is, see: Letterbooks, Indexes, and Learning about Early American Business | The New York Public Library (nypl.org)