The Life and Loves of Lafayette

Lafayette periodically regains the limelight in American culture. He has found his way to popularity again recently, and as his name is bounced around the internet, he often finds himself included with LGBT+ historical figures from his era. There is something about Lafayette that makes us want to categorize him this way; maybe it is a sense that we get. But are there really facts to support the idea that Lafayette was LGBT+? And if so, where exactly does he fit under the rainbow? We can get closer to answers to these questions by looking at Lafayette’s relationships with his wife, his mistresses, and his closest male friends, but nothing is as it seems in Lafayette’s story, and ultimately he may have much to teach us about how we approach the search for LGBT+ history.

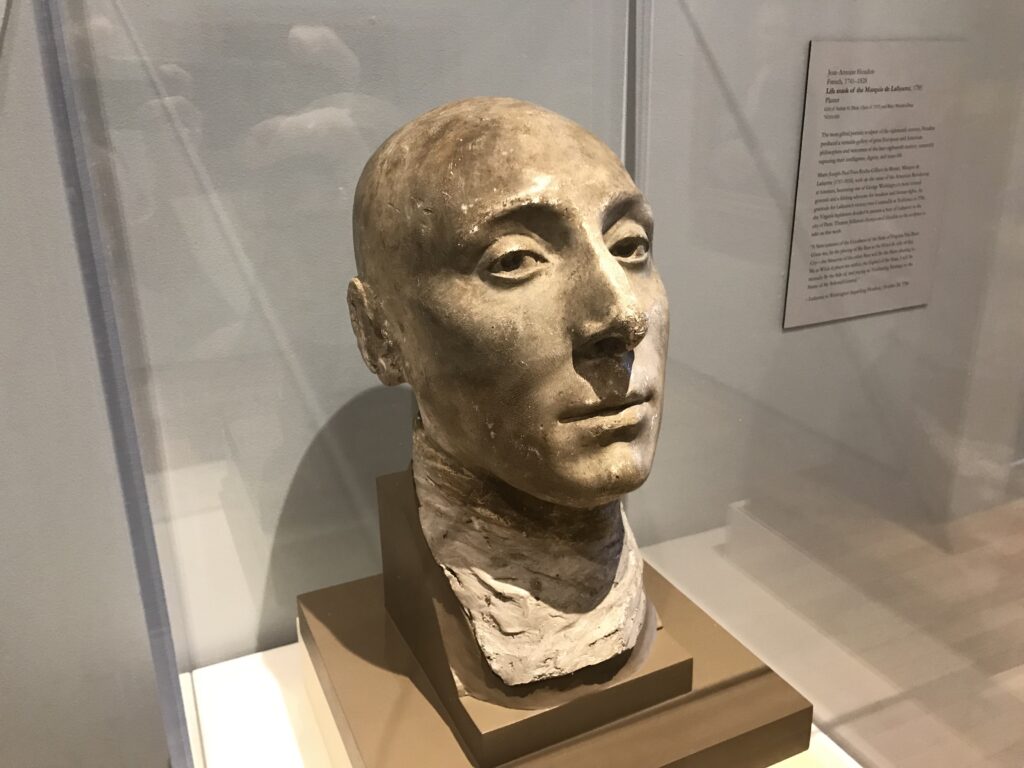

Who was Lafayette?

Lafayette was born in Chavinac, France, on September 6th, 1757. Raised by his paternal grandmother, Lafayette lived in Chavinac until he was six years old, when his mother called him to Paris to begin his life as a high society gentleman. Lafayette married Adrienne and the couple had two children by the time Lafayette snuck out of France to prove himself in the American Revolution. During Lafayette’s occasional visits to France during the war he fathered two more children, and after the Battle of Yorktown he returned to his family. After that Lafayette found himself swept into the heady current of French political reform. Lafayette became an integral part of the French Revolution, but for all his merits he was an indecisive leader, and eventually the people turned against him. Lafayette was forced to flee, was captured by the Prussian military, and found himself in prison for the next five years. He eventually returned to France and once again found himself at the center of politics, eventually playing a valuable role in the installation of King Louis-Phillipe. After this his political power dwindled, and Lafayette lived a quiet life until his death on May 20th, 1834.¹

His Wife

When Lafayette was fourteen, his grandfather began trying to find him a wife. As his mother and then several members of her family had died, Lafayette had inherited fabulous amounts of wealth and power, and so his grandfather set out to help Lafayette marry into a family whose stature and connections would allow Lafayette to climb the final rungs to the uppermost reaches of society. He found the Noailles, a family that had established itself as the height of wealth and power by being consistently in the king’s favor. Negotiations were made, and Lafayette became engaged to the youngest daughter of the family, Marie Adrienne Françoise de Noailles (known as Adrienne). Noailles was only thirteen when the marriage was finally agreed upon by the two families, so it was agreed that the wedding would not take place for two years. During this time Lafayette lived in the enormous Noailles mansion, but he was rarely allowed to see Adrienne, who lived in a different wing of the mansion and who was not initially told that the reason Lafayette had moved in was because he was her fiance. On April 11th, 1774, Lafayette and Noailles were married. She was fifteen and he was seventeen.²

The marriage was arranged to unite wealthy and powerful families; the bride and groom barely knew each other before their marriage; and they were still children when the marriage was negotiated. Clearly, their union did not start out with love. But did the Marquis and Marquise grow to love each other? It certainly seems like they did. At the time, it was common for upper class husbands and wives to live completely separate lives. Everyone knew a rich couple’s marriage had been arranged for the pooling of wealth, and no one expected them to be in love. The sheer size of the Noailles household, in which the couple continued to live for several years, made having nothing to do with each other very possible. But Lafayette never did that. When he was there, Lafayette spent time with his wife, and by all accounts they got along well.³ When he was in America, Lafayette sent long, emotional letters to his wife. Because the King had forbidden him to go to America, Lafayette escaped France secretly without telling his family he was leaving. While he was away Lafayette wrote his wife letters begging her to tell him she still loved him, in one telling her that though he loved America “I miss you, my dear heart, I miss my friends; and there can be no happiness for me away from you and them. I ask whether you still love me, but I ask myself the same question far oftener, and my heart always answers that you do. I hope that is right.”⁴

Of course it is possible that their love, though strong, was not romantic or sexual, particularly on Lafayette’s side. Lafayette had been very alone for a long time. After being summoned away from the only guardian he really knew to move to Paris, Lafayette found himself in a world where he did not fit in at all. He was not good at any of the skills gentlemen in Paris were supposed to have mastered, especially the ability to socialize. Lafayette was awkward and shy, and was known for lapsing into long silences. His only friend in this strange new world was his mother, but she passed away when he was still quite young.⁵ Suddenly, he found himself thrown together with a girl who by all accounts adored him just the way he was.⁶ It would make perfect sense for Lafayette to enjoy spending time with Noailles and to miss her when he was far away even if he was not attracted, sexually or romantically, to women. Still, with the evidence currently available it would not make sense to completely dismiss the possibility that Lafayette was genuinely interested in his wife. Therefore, even if Lafayette was LGBT+, it is likely he was not gay.

His Mistresses

When Lafayette was brought to Paris to learn to be a proper noble gentleman, he was confronted with a list of seemingly unattainable qualifications. Not only did he need to be a socialite, he needed to be a skilled horse back rider, a graceful dancer, and a debaucherous playboy. Lafayette failed miserably at the first three things; aside from his non-existent social skills, he was a boringly adequate rider and tripped over his own feet while dancing with Marie Antionette.⁶ Desperate to belong, Lafayette set out to meet the final qualification, and prove to all of his friends that he was as adept a womanizer as any man in Paris.

Lafayette met Aglaé de Hunolstein not long after his marriage. Hunolstein was at that point in a relationship with a prince of the blood, and so was unimpressed by the shy, awkward Lafayette, who was socially inferior to her current lover. In fact she barely took notice of him, despite his attempt to impress her by trying to force one of his friends to duel him over her.⁷ This changed after Lafayette’s first sojourn in America. After serving in the Continental Army for about a year, Lafayette made a trip back to France during the winter of 1778, since fighting would not resume until spring. When Lafayette arrived back in France he was heralded as a hero. Seeing Lafayette was quickly becoming a celebrity, Hunolstein changed her mind about him, and the two began having an affair. This affair lasted several years, and during this time it became incredibly scandalous. An elite, Parisian gentleman like Lafayette was supposed to have a mistress, and was supposed to show off a little when he got one; even by these standards, Lafayette and Hunolstein were apparently too obvious in their relationship. The gossip surrounding the affair began to badly damage Hunolstein’s reputation, and she became unhappy. As is usually the case with such things, Lafayette’s reputation did not fare as badly, and the relationship began to turn ugly when Lafayette refused to let Hunolstein end the affair. They spent most of the next year fighting, though Lafayette continued to insist there was no reason for them to break up. Eventually, Lafayette ended the relationship; he had found someone new, and the affair with Hunolstein had become, in his eyes, more trouble than it was worth.⁸

Not long after his break up with Hunolstein, Lafayette began an affair with Diane de Simiane. Simiane was married to the Marquis de Miremont. Just like with Hunolstein, the reason Lafayette began trying to woo her had nothing to do with her. Lafayette later admitted when describing the relationship “I wanted at first to triumph less over the object herself than over a rival…”⁹ Lafayette charmed her away from whoever this rival was to prove that he could. Their affair was probably sexual initially, but at this time in France politics were beginning to heat up, and Lafayette was away on business for most of the time he and Simiane were supposedly having an affair. Instead their relationship mostly took the form of letters, and not particularly sexually charged letters either. Rather their letters were mildly affectionate, and consisted mainly of Lafayette asking Simiane for political advice and emotional support. He obviously respected her more than he did Hunolstein, and as the sexual component of their relationship faded away they became good friends. Lafayette’s lack of sexual interest in her did not bother Simiane because she had consented to the affair largely as a political maneuver. Simiane believed that Lafayette would end up at the forefront of French government as soon as the political reform taking place was over, and she wanted to be closely connected to him when he did. Their friendship encountered some obstacles as the revolution heated up and they took opposing sides, but when the Reign of Terror ended and the dust settled, they decided to put politics aside and be friends again. The idea that they ended up as friends rather than lovers is bolstered by the fact that Lafayette’s wife, who was apparently upset by his affair with Hunolstein, actually liked Simiane. Noailles visited Simiane on her way to join Lafayette in prison, and when the Lafayettes had a home again, Simiane actually came to live with them briefly. Adrienne told her children to call Simiane “aunt,” and some of her last words to her husband were to give Simiane her love.¹⁰

Lafayette’s relationships with his mistresses do not prove he was attracted to women because they prove nothing about his sexuality at all. Lafayette had the affair with Hunolstein to prove his elite status and masculinity to his peers in Paris. He had his affair with Simiane to assert his superiority over some other man. That these affairs were a show for Lafayette’s peers in Paris is further reinforced by the fact that Lafayette never had a mistress outside of France. Lafayette spent extended periods of time on a completely different continent from his wife; many men even today would see this as a time when it is perfectly acceptable to have an affair. And yet, Lafayette appears never to have had an American mistress. None of Lafayette’s reasons for taking mistresses had anything to do with love or lust, and Lafayette likely would have done the same thing no matter his sexual and/or romantic identity.

His Male Companions

Lafayette met George Wahsington in the summer of 1777. Lafayette initially annoyed the General, as he consistently badgered Washington to give him a field command (a power which rested with Congress), but eventually Washington came to see that Lafayette’s over-enthusiasm came from a real desire to be useful.¹¹ The letters they wrote one another whenever they were separated from that point on are a powerful testament to their unshakable love. This is particularly true of Washington’s letters; Lafayette was a very affectionate person, and was in the habit of including his love in letters to almost everyone he did not dislike. Washington on the other hand was so far from being emotional that he was widely known for his cool and detached demeanor. Washington’s early letters to Lafayette do not contradict this; when they are actually from him, they are short and business-like, but more often than not they were actually penned by one of his aides de camp. By the end of his decades-long correspondence with Lafayette, Washington was writing the Marquis very long letters filled with unbridled affection. This is so remarkably out of character for Washington that it cannot be denied that he loved Lafayette, and Lafayette definitely seems to have loved him back.

But was this love romantic? There are two popular theories about Lafayette and Washington’s relationship: that they were lovers, and that they were more like a father and son. Reading their letters one can definitely find evidence to suggest that they were lovers. For instance, Washington and Lafayette occasionally refer to one another as “the man I love.”¹² There is a noticeable difference in telling someone you love them and referring to them as the person you love. Certainly the former would have been more typical of correspondence between close male friends of the time than the latter. There was also a strange, romantic banter between the two centering on Lafayette’s wife. In one letter Lafayette tells Washington “I have a Wife, My dear General, who is in love with you, and affection for you Seems to Me So well justified that I Can’t oppose Myself to that Sentiment of her’s.”¹³ It almost seems like he is flirting with Washington under the guise of relating the feelings of his wife, and the General does not miss this. In a subsequent letter Washington replies: “Tell her (if you have not made a mistake, & offered your own love instead of hers to me) that I have a heart susceptable of the tenderest passion…”¹⁴ Washington actually suggests here (however jokingly) that when Lafayette said Noailles was in love with Washington, he actually meant he was. In light of this comment, one could infer that later on when Washington laments that “no instance can be produced where a young woman from real inclination has preferred an old man,” he is actually asking if Lafayette could be genuinely attracted to him.¹⁵

Aside from these things their letters are peppered with comments that seem more romantic than friendly or familial. This includes such things as Lafayette telling Washington: “Never Could any Being in Creation love you more, Respect you more than I do,”¹⁶ and Washington jealously asking Lafayette “When my dear Marquis shall I embrace you again? Shall I ever do it? or has the charms of the amiable & lovely Marchioness—or the smiles and favors of your Prince with-drawn you from us entirely?”¹⁷

On the other hand, Lafayette does sometimes outright refer to Washington and himself as father and son, and to the love between them as filial. In fact, Lafayette did this at least a dozen times just in the decade or so of their correspondence that I read. Lafayette began saying things like “filial love” and “adopted son” about five years into his acquaintance with Washington, and from that point on did it somewhat regularly. Since the evidence I have already given regarding the possibility that they were lovers seems so strong, it does not seem right to state unequivocally that their relationship was that of a father and son. Still, what reason would Lafayette have to describe it as such, particularly in his private letters to Washington, if that is not what it was? It is interesting to note that Washington never did this in his letters. The only example of Washington referring to Lafayette in these terms is from a story told by Lafayette and others in which, after Lafayette was shot in the leg, Washington told his surgeon to treat Lafayette as though he were Washington’s son.¹⁸ Even if Washington really did say this, however, it does not prove much: if Washington considered Lafayette his lover, he certainly could not have said this to the surgeon and in front of lots of other people.

With all of this conflicting information it is hard to say for sure what Lafayette’s relationship to Washington was. That they loved each other cannot be disputed, no matter the way in which this love manifested itself. It is also important that we do not assume that once love reaches a certain level of intensity it must be romantic, the notion behind the phrase “more than friends.” The love between friends is not restricted to a maximum level of feeling, and can be just as intense or even more so than that between lovers. It is also possible that there is more to this story, and that Lafayette and Washington themselves disputed the nature of their relationship. Writing for The Advocate, Jacob Ogles suggested that Washington and Lafayette were not lovers, but that Lafayette wanted them to be.¹⁹ It is entirely possible that Lafayette wished to make their relationship romantic but that Washington refused. Washington’s suggestion that a young lover could never be truly happy with an older one may shine a light on what their relationship was really like. Perhaps Lafayette often told Washington he was in love with him, only to have Washington rebuke Lafayette, telling the young Marquis that he did so for Lafayette’s own good. It is then possible that Lafayette referred to their relationship as “filial” so often to gently mock Washington for refusing to let it be anything else. The reverse is also possible; perhaps Washington wanted to be lovers and Lafayette did not, and so Lafayette calls himself Washington’s “adoptive son”²⁰ to gently remind him their relationship should never be romantic. This could be why, after Lafayette gives Washington his wife’s love, Washington asks if Lafayette really meant that he loves the General; Washington wants Lafayette to admit he is in love with him, but Lafayette will not. The reality could have been either of these options, a cross between the two, or some third option. A valuable takeaway from this is that when trying to determine whether a relationship was romantic or friendly, it is important to keep in mind that the very people in that relationship may not have been clear on it either.

It has also been suggested that Lafayette was also romantically involved with his two best friends, Alexander Hamilton and John Laurens. Hamilton’s grandson Allan McLane Hamilton called them “the gay trio.”²¹ The theory that Lafayette was romantically involved with Laurens at least seems relatively unfounded. There is nothing to suggest that Laurens had romantic feelings for Lafayette, and certainly none of his interactions with the Marquis compare to his interactions with Hamilton as far as suggestions of romance go.²²

Hamilton’s correspondence with Lafayette is a little more compelling. They certainly were affectionate with each other, with Lafayette once telling Hamilton “Before this campaign I was your friend and very intimate friend, agreable [sic] to the ideas of the World. Since my second voyage, my sentiment has increased to such a point, the world knows nothing about. To shew both from want and from scorn of expressions I shall only tell you. Adieu.”²²⁺ It is hard to say however where the line between acceptable friendly affection and romance is for Lafayette. At one point during the war, when apologizing for a mistake he made, Lafayette told the French general Rochambeau “If I have offended you, I apologize, for two reasons, the first, because I love you.”²³ Lafayette was not like Washington or Laurens; he freely dispensed love to all who had his esteem. Therefore, determining when Lafayette was in love with someone as opposed to when he loved them as a friend or family member is different than figuring out the same thing for another person. A final thing to consider is that Lafayette did describe his relationship with Hamilton as brotherly. Assuring Hamilton that their differing opinions on the French Revolution would not be the end of their friendship, Lafayette told him “that from the Early times Which Have Linked our Brotherly Union to the last Moment of my Life I shall Ever be, Your affectionate friend, Lafayette.”²⁴ While of course to the public a same-sex couple of the time would have had to pretend their love was, for instance, brotherly, in a private letter it does not make sense for Lafayette to unnecessarily add that they were like brothers if he actually thought of Hamilton as a lover.

What the “gay trio” really seems to represent is not polyamory but queer kinship. Lafayette may have been LGBT+, and Hamilton and Laurens definitely were. This may have been one of the many reasons that the three were drawn so closely together. At one point during the war Lafayette said to Hamilton of Washington that “you know how tenderly I love him.”²⁵ Was it a coincidence that Hamilton mirrored this sentence two years later when he told Lafayette of Laurens’s death and said “You know how truly I loved him”?²⁶ It seems that in Hamilton and Laurens, Lafayette found friends with whom he could discuss any non heterosexual/romantic feelings he may have had, and this may have been something Lafayette sorely needed.

One of the biggest takeaways from Lafayette’s story is that human relationships are complicated, and therefore so is the process of uncovering them. Lafayette’s relationship with his wife feels like it should prove beyond the shadow of a doubt that he was romantically and sexually attracted to women, but it cannot be overlooked that there may have been non-romantic, non-sexual reasons that Lafayette loved Noailles. His relationships with his two mistresses also feel like they should prove at least sexual attraction to women, but they also fail in this respect because Lafayette used these relationships for reasons altogether unrelated to sex or romance. Lafayette’s relationships with men introduce complications as well. We can look at his correspondence with George Washington and decide whether or not they actually embarked on a romance, but will that tell us whether or not they were attracted to each other? It is entirely possible that their relationship was not what one or both of them wanted. Lastly, Lafayette’s relationships with John Laurens and Alexander Hamilton respectively serve as a reminder of a fact that some historians forget too often: just because two historical figures were, for example, male-attracted men, does not mean that they were in a relationship with each other. We take for granted as we look around our modern world that LGBT+ people are drawn together for support, solidarity, and camaraderie; it is easy to forget that LGBT+ people of the past came together for friendship too.

All this is not to say that we can never know a historical figure’s identity; if we succumb to this kind of thinking, the entire field of history begins to feel pointless. What the confusion Lafayette’s story leaves us with can tell us though is that if we want to uncover lost LGBT+ history we must go beyond surface level assumptions about relationships and be ever more open to appreciating the complications of human life.

If you want to help me continue searching for lost LGBT+ history, please consider becoming my Patron! 18th Century Pride is creating LGBT+ History Content | Patreon

1-7. Lafayette: Hero of Two Worlds, Olivier Bernier

8. “Marquis de Lafayette and His Affair with Aglaé of Hunolstein”, Sarah Murden and Geri Walton, https://georgianera.wordpress.com/2017/03/23/marquis-de-lafayette-and-his-affair-with-aglae-of-hunolstein/

9. The Marquis: Lafayette Reconsidered, Laura Auricchio, https://erenow.net/biographies/the-marquis-lafayette-reconsidered/12.php

10. See #1-7, and “Lafayette and Diane of Simiane: Their Love Affair”, Geri Walton, https://www.geriwalton.com/love-affair-lafayette-and-diane-of-simiane/

11. See #1-7

12. Washington to Lafayette: From George Washington to Lafayette, 4 January 1782, https://www.founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-07649

Lafayette to Washington: To George Washington from Lafayette, 9 December 1780, https://www.founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-04173

13. To George Washington from Major General Lafayette, 12–13 June 1779, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0126

14. From George Washington to Major General Lafayette, 30 September 1779, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-22-02-0472

15. Ibid.

16. To George Washington from Lafayette, 19 March 1785, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-02-02-0305

17. From George Washington to Major General Lafayette, 4 July 1779, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0286

18. “My Dear General: the relationship between Lafayette and Washington”, Lynn H. Miller, http://francerevisited.com/2009/08/my-dear-general-the-relationship-between-lafayette-and-washington/

19. “15 Gay Founding Fathers and Mothers”, Jacob Ogles, https://www.advocate.com/arts-entertainment/2018/2/02/15-gay-founding-fathers-and-mothers

20. To George Washington from Lafayette, 16 April 1785, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-02-02-0362

21. The Intimate Life of Alexander Hamilton, Allan McLane Hamilton, Quoted in Alexander Hamilton, Ron Chernow, 96

22. https://john-laurens.tumblr.com/post/137582076443/is-there-any-historical-evidence-for and https://john-laurens.tumblr.com/post/136305824523/i-was-just-curious-if-you-know-anything-about-the

22.+ To Alexander Hamilton from Marquis de Lafayette, 28 November 1780, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-1004

23. See #1-7

24. To Alexander Hamilton from Marquis de Lafayette, 12 August 1798, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-22-02-0046

25. To Alexander Hamilton from Marquis de Lafayette, 9 December 1780, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-1006

26. From Alexander Hamilton to Marquis de Lafayette, [3 November 1782], https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-03-02-0102

Pupbee.paws

Thank you so much for addressing his complicated relationship to Washington and how it suddenly changed. I too noticed that in their correspondence, after the war when he returned to France, he started signing his letters with “filial” affection and referring to himself as a “son.” I find myself wondering what really happened to cause this change, and I love that you listed some theories, because I share them (plus more! I have so many theories, lol). Personally I think they were romantically in love, but obviously there is no proof as to whether that relationship became sexual. I do think they “broke up” so to speak after the war and remained in love, but made a choice to change the perimeters of that love (from seemingly romantic to father/son). Of course, this itself begs the question of whether or not the title was purely used as a cover story to protect themselves from rumors, but either way, the shift did happen. I’m glad you have not dismissed the notion entirely that they may have been romantically in love in the beginning (during the war). Like you said, feelings change, situations change—especially during wartimes when you don’t know if you’ll live to see the end of it. There are so many factors that contribute to people pursuing relationships both homosexual and heterosexual (or homoromantic and heteromantic, to be more inclusive).

I appreciate your insight on his relationship to Hamilton and Laurens (The Gay Trio)! I used to wonder about them being romantically involved (more so with Hamilton because I couldn’t find much about him and Laurens. Still haven’t uncovered any of their allegedly romantic letters), but reading your work, I agree that it was likely more of a “support group” relationship. They likely felt comfortable around each other and safe in expressing their feelings. Like you said, just being friends with other people in the LGBT community, and receiving that validation and acceptance is so important.

Thank you for sharing all your research! I continue to dig around for documentation of LGBT+ throughout history myself. I’m glad to see someone else who cares about this subject. It’s so painful and frustrating to see historians, whose job it is to relay facts not opinions, assume everyone throughout time was straight (especially through the flimsy excuse of “well he was married, so….obviously straight!”). I mean, obviously being married doesn’t prevent anyone from still being attracted to other people (regardless of gender). And in times where being not-straight is socially unacceptable and in most cases punishable, it goes without saying those people will hide their relationship. Historians seem to conveniently forget that both crimes and illicit affairs have been happening since the dawn of time, and plenty of people have gotten away with both, so….secretly being gay/bi is entirely plausible for literally every historical person. It’s not something they would have had a concrete record of (since you know, needs to be kept secret).

I just have to say one more thing (sorry for such a tedious comment), because I saw you address this on your Instagram. The whole “everyone wrote like this back then. It was normal for men to be excessively affectionate.” ……that’s literally admitting that everyone was gay. If everyone was doing it, then the evidence is right there. How can they refute it. What historians should be saying is….idk, everyone used to be gay/bi and gradually shifted to being less affectionate towards the same sex? At least acknowledge it rather than trying to deny it?? Like, now that we of modern times have vocabulary for such behaviors and feelings, go ahead and label it as such. If you’re saying they were affectionate, that’s a pretty clear admittance that okay, guess everyone was gay/bi. Saying that everyone essentially acted gay because it was normal for the times doesn’t mean they weren’t gay, it means they WERE gay. What kind of backwards reasoning…That’s not how facts work?? You know what I’m saying, right? Because it honestly “straight historian reasoning” makes no sense to me and I don’t know how to explain such a nonsense theory. I don’t know how people are so blind to their own words.

Sorry if I over shared and rambled! Just to clarify, I was using the word “gay” as a general term for “homosexual behaviors”, I don’t mean in any way to exclude bisexual people or discriminate against the many romantic orientations or relationships that are purely emotional and not necessarily romantic. I certainly wasn’t implying that gay relationships have to be sexual. I also don’t know if you prefer the word “bi” or “pan,” so again, apologies if I have used incorrect or over-generalized terms. That wasn’t my intention.

Hope my comment isn’t too long. I could honestly discuss this all day, but I don’t want to bore you!

megangack

It defeinetly is possible that they were in a romantic relationship at some point, and that the shift in language in their correspondence happened when the nature of their relationship changed. It is strange how Lafayette spent several years never using that kind of familial language and then suddenly included it in almost every letter.

I’m so glad you enjoy my work! It always hurts a little when I get a new book on history and I already know that they are either going to leave out LGBT+ history or address it just to deny and erase it. That’s why doing this work is so important to me.

I do think that the 1700s had different standards for what (particularly male) friends could say to each other, so there is going to be a lot of sweet, flowery language between men who really were friends; that much historians are right about. What gets annoying is when they use this to deny the possibility that ANY two historical figures had a same-sex relationship. Historians will honestly go to ridiculous lengths to avoid having to acknowledge that some historical figures may have been LGBT+, often by creating standards for proving relationships that are impossible to meet.

Thank you for your comments, it’s great to know that someone is actually reading my articles and learning from them!

(P.S I prefer to use “LGBT+” rather than “gay”, just to make sure I’m not leaving anyone out. I know you weren’t intentionally excluding anyone though.)

Pupbee.paws

I’m so sorry for coming back, I wanted to say one more thing and ask if you have any knowledge of this. I read recently that it has not been uncommon throughout history for gay couples to legally adopt their partner, so that they can have the legal rights as a spouse would have. Have you heard about that at all? The cases I read about were all from the 1900’s, but I noticed Von Steuben adopted William North and Benjamin Walker, whom with which he was supposed to be in a romantic/sexual relation. My source is this: https://www.history.com/news/openly-gay-revolutionary-war-hero-friedrich-von-steuben I’m really curious to know if you have any insight, because I was not aware of this practice until yesterday. It got me wondering if calling someone father/son had the same “code word” effect of labeling them “brothers” to disguise the fact they were dating. As I’m sure you know, the media LOVES to label any homosexual couple as “brothers” or “sisters” because straight people can’t see gay. So yeah, it might be a possibility that in signing his letters as “filial”, Lafayette may have been affirming rather than denying his romantic attachment, but I don’t have enough insight or evidence. Just wanted to throw it out there.

megangack

As a matter of fact I have heard a number of stories of people legally adopting their same-sex partner so they could have some of the legal benefits of spouses. Like you I have mostly heard stories of this happening in the 1900s, but as you pointed out Steuben did make use of this strategy to insure some of the men in his life would inherit his property.

Whether this legal strategy ever led to people calling their partners “father/son” or using “filial love” as code for romantic love I do not know, but it is possible. I certainly don’t think we can write off Lafayette and Washington’s relationship as not being romantic just because Lafayette referred to their relationship the way he did.

anniscold

Ok, first off, I love this site, it’s amazing. I absolutely love the article about Laurens’ sister, since I read his biography and noticed. There’s so much queer history we don’t know about. I honestly wish I could comment on the entire blog at once, and the possibility of Madison being ace, since I’ve read a lot about it, but he is honestly one of the most confusing (and brilliant tbh) Founding Fathers. This blog is really interesting, especially for a LGBTQ+ person who loves history.

megangack

Thanks, I’m so glad you enjoy my work!

Yeah, I read Massey’s biography of Laurens and that part really jumped out at me! I didn’t really reach a definitive answer though, maybe I’ll circle back to her eventually.

I ended up not being totally sure if Madison was ace, but I enjoyed writing that article because ace history isn’t something I’ve really thought about before. How to know if a historical figure was ace is something that still alludes me.

I’m glad you find my writing interesting, there is definetly a lot of LGBT+ history that needs to be rediscovered. Thanks for the comment!

Were marquis de lafayette and hamilton friends? Explained by FAQGuide

[…] Source: https://www.18thcenturypride.com/the-life-and-loves-of-lafayette/ […]