Robert Shurtleff’s Other Secret

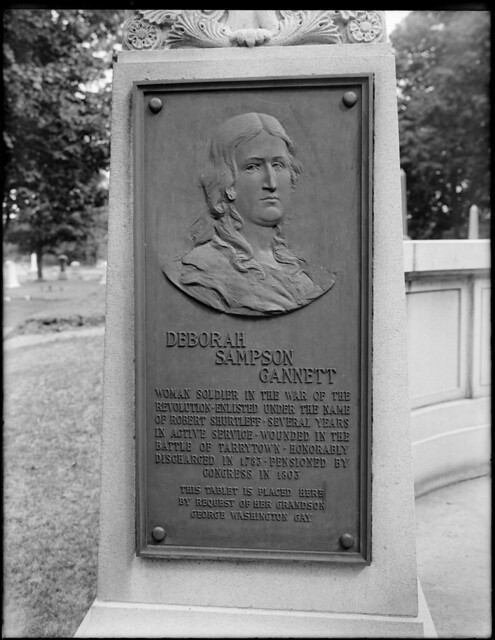

Though sometimes overlooked, in recent years Deborah Sampson Ganett has been held up as a feminist icon in American history, and rightfully so. One of the few women known to have served as a soldier in the Revolutionary War, Sampson is a stunning example of a woman in the late eighteenth century who recognized that she was unfairly limited due to her sex and refused to live her life by society’s rules. But is it possible that Sampson may deserve to be heralded as a bisexual or lesbian icon as well?

Deborah Sampson, later Deborah Ganett, was born on December seventeenth, 1760, in Plympton Massachusetts. Her family was poor, and in an attempt to alleviate their situation her father became a sailor, only to be lost at sea not long after. His death caused their situation to become truly desperate, and Sampson’s mother was forced to hire out the children as indentured servants. Sampson’s indenture ended when she turned eighteen, and for a time she worked as a teacher.¹ Sampson longed to experience more of the world than just the town she grew up in, and so in 1782 she disguised herself as a man and enlisted in the 4th Massachusetts Regiment of the Continental Army, under the name Robert Shurtleff. Sampson served until 1783, and distinguished herself as a capable and brave soldier.² During her time as a soldier, she desperately avoided exposure, once digging a bullet out of her own leg so there would be no need for a doctor to remove her clothing. After contracting a fever, however, Sampson lost consciousness and was undressed in a hospital, revealing her true sex. Sampson’s commander was more surprised than angry at the revelation, and though she was discharged almost immediately, she was discharged honorably.³

Gender Identity

Before discussing Sampson’s sexual and romantic orientations, it is necessary to address the subject of her gender. Obviously her cross-dressing does not prove that she identified as a man, but it does raise some questions. In an interview with Advocate on his novel about Sampson, Sampson’s descendant, transgender rights advocate Alex Myers, addressed these questions. Myers explained, “…it seems to me that she was not really choosing between being a man and being a woman. I think she was choosing to be enslaved or free. To be a woman at the time was to have no freedoms. I think by disguising herself as a man, it was less of her saying ‘I want to live as a man,’ and more that she wanted to have personal freedom and independence.”⁴

Upon leaving the army, Sampson briefly continued to live as a man, but later went back to living as a woman voluntarily.⁵ That being said, it should never be assumed that a cross-dressing soldier is just a woman who wanted to break out of social bonds. Of the many crossing dressing soldiers assigned female at birth who have been discovered, either at the time or by historians later, many have turned out to be transgender men. In Sampson’s case however, it seems that she did identify as female, but did not feel that being female should constrain her to a specific set of experiences.

Shurtleff the Charmer

More than a decade after leaving the army, Sampson co-wrote the story of her life with a writer named Howard Mann. This book, The Female Review: Life of Deborah Sampson The Female Soldier in the War of the Revolution, contains a lot of the evidence that exists of Sampson’s orientation. The first hint of this is when The Female Review suggests that Sampson enjoyed it when women found her male persona attractive.⁶ That being said, the book was clearly intended to be sensational, and the mentions of Shurtleff’s appeal to women almost feel like jokes. Mann intends for the audience to be amused by the fact that women are falling in love with this handsome man, who they have no idea is actually a woman. Thus these mentions do not reveal much about Sampson’s attractions.

Shurtleff’s Romance

As the book goes on, a more perplexing element emerges. Somewhere along Sampson’s journeys with the army she meets a woman, referred to only as Miss P., and a romance develops.⁷ Mann changes many details of the romance for the purposes of his story, but the editor of the 1916 edition, John Adams Vinton, included footnotes comparing the final book to the original manuscript, and they help to shed some light on the details Sampson originally provided Mann with. While Mann presents the situation as yet another woman throwing herself at Sampson, who must scheme her way out, according to Vinton the original manuscript reveals “that [the two women] became mutually and tenderly attached.”⁸ Around this time was when Sampson fell ill. After Sampson’s recovery, P. invited Sampson to meet with her, and at this meeting confessed her love for Sampson.⁹ In the original manuscript, Sampson explains her reaction to this event, telling her audience that she could not bear to break the woman’s heart, or to “refuse the affection so warmly proffered, and so delicately expressed.” Instead she spent two days with P., and then left on a journey west, promising to visit her again when she returned.¹⁰

When Sampson eventually did return, she tried to get P. to lose interest in her, but this did not work.¹¹ The situation caused Sampson a lot of pain. In the original manuscript, Sampson tells her audience, “It is no matter how I felt, or what I said, or did on this occasion. I could not, if I would, describe either.” She realized she had to tell P. her secret. The next day she returned to her, and actually took off her clothes in order to prove to P. that she was in fact a woman. After that, they parted ways.¹²

More telling than the details of their break up however may be that Sampson said her and P. “became mutually and tenderly attached.” This statement seems to lend credence to the theory that Sampson did return P.’s feelings, though she knew the relationship would never work.

Shurtleff Gains a Reputation

After receiving her discharge, Sampson went to live with her uncle. Sampson claimed to be her youngest brother, Ephraim Sampson, and continued to live as a man for a time.¹³ During this time Sampson apparently earned herself quite a reputation with women.¹⁴ Mann finds himself at a loss to explain these relationships, because he blatantly does not believe that a woman could be attracted to other women.¹⁵ He does however admit that Sampson’s uncle frequently reprimanded her for her behavior with the young women of the village, and even suggests that her correspondence from the time (which does not survive) went way beyond what Mann felt is proper between two women.¹⁶ The original manuscript concurs that “She passed the winter doing farm work, and flirting with the girls of the neighborhood.”¹⁷ These relationships are different than other things in the book because they are not women pursuing Sampson, they are Sampson pursuing women, with no apparent motive other than attraction.

Looking at The Female Review

It is important to consider the lens through which this information comes to us. As I already explained, entertainment is likely the reason for some of the little references to women being attracted to Sampson. Mann also tries to make Sampson’s relationship with P. and her interactions with women after the war shocking and dramatic. It is actually possible that, although he may not have really believed women could be attracted to women, Mann hoped to make use of the homoerotic implications of Sampson’s story. While lesbains may not have been at the forefront of culture in the late eighteenth century, it was not an unknown concept, and sexual relationships between women often found themselves the centers of erotic and even pornographic writing aimed at straight audiences.¹⁸

Mann is also biased because, as mentioned above, he blatantly states at several points in the book that he does not believe a woman could be attracted to another woman. Thus Mann presents every possibly romantic or sexual interaction with a woman that Sampson has as being entirely on the side of the other woman.

Sampson’s credibility is a much more complicated subject. For the most part, it seems that Sampson only lied to make her military career seem more impressive. For instance, Sampson claimed to have served at the Siege of Yorktown, but historians now know she did not even enlist until after it had happened. But this lie about her career complicates other things; Sampson claimed to have first met P. while the army was on its way to Yorktown.¹⁹ Does this call into question Sampson’s other statements about that relationship?

Sampson’s Later Years

Sampson spent the winter after leaving the army living as her brother, but by spring she had decided to go back to being Deborah Sampson. It was now 1784. About a year later, on April seventh of 1785, Sampson married Benjamin Ganett. They had three children, Earl, Mary, and Patience, and adopted a baby named Susanna.²⁰ Sampson had retired to a life typical of a woman of her time. The only unusual thing Sampson did in this last part of her life was to occasionally travel to cities and give performances. Sampson would tell her story, sometimes in a dress and sometimes in full military regalia, and would demonstrate her skill at manuel drill.²¹

The available evidence strongly suggests a romantic relationship between Sampson and Miss P., rather than proving one. Sampson’s habit of flirting with women, while likely fact, does not necessarily indicate that she was attracted to women. That being said, those these things may not prove Sampson was romantically and sexually attracted to women, they do present some solid evidence. While Sampson’s homo/bisexuality may not be ready to be presented as definitive fact, it is a strong enough possibility that it needs to be considered by anyone hoping to write about Deborah Sampson Ganett in the future.

If you appriciate what I do here, please consider becoming my Patron! 18th Century Pride is creating LGBT+ History Content | Patreon

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Deborah-Sampson, “Deborah Sampson”, Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica

- For Sampsons reason for enlisting see: The Female Review, Howard Mann, 85, Note #30, by editor John Adams Vinton. For the other facts about her military career see: Citation #1

- See #1

- https://www.advocate.com/books/2014/04/21/was-americas-first-female-soldier-also-lgbt, “Was America’s First Female Soldier Also LGBT?”, Michelle Garcia

- Mann, 161

- Ibid., 97

- Ibid., 137

- Editor John Adams Vinton, 137-138, Note #98

- Mann, 141

- Ibid., 143

- Editor John Adams Vinton, 152-153, Note #114

- Editor John Adams Vinton, 153, Note #116

- See #5

- Mann, 161

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Editor John Adams Vinton, 161, Note #126

- www.jstor.org, “Mapping an Atlantic Sexual Culture: Homoeroticism in Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia”, Clare A. Lyons, 28

- See #8

- https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/deborah-sampson, “Deborah Sampson”, Debra Michals PhD

- Diary of Deborah Sampson Ganett in 1802, Deborah Sampson