Learning From Roderick Random

The novel The Adventures of Roderick Random by T. Smollett was an incredibly popular book for its time, and so is a valuable resource for modern readers hoping to learn about the culture of the mid-to-late century in the places in which it was sold. This makes the book’s references to LGBT+ topics particularly interesting; Roderick Random showcases its society’s stereotypes, misconceptions, and language surrounding LGBT+ people. All of these things come together to help us understand that in the mid-to-late seventeen hundreds, LGBT+ people were surprisingly visible.

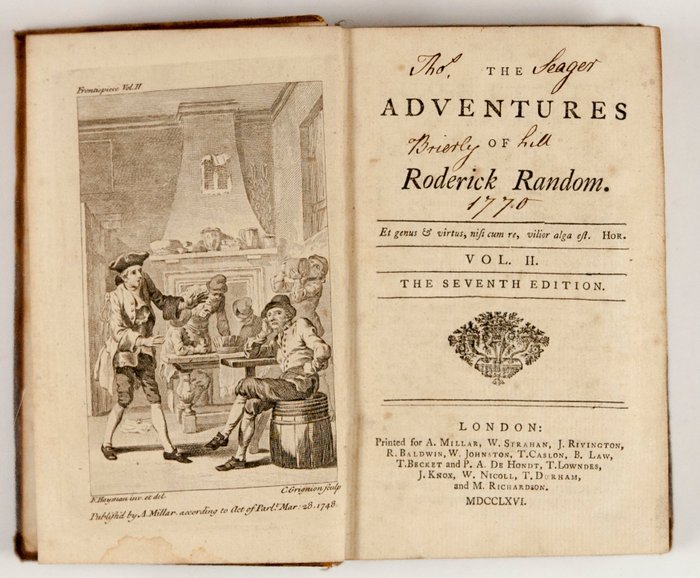

The Adventures of Roderick Random is a British book by a British author, but the book is still definitely relevant to American LGBT+ history. Like many popular British novels of the day, Roderick Random made it to America, and the multitude of ads booksellers ran for it show it was incredibly popular there. The book was cheap enough that merchants and skilled tradesmen could afford it, but that was not the only way people could get their hands on it: Roderick Random was owned by many subscription libraries, where patrons could pay a small fee to borrow the book. Records from some of these libraries show it was exceedingly popular.¹ Thus many Americans, cis-het and LGBT+ alike, were exposed to the LGBT+ representation in Roderick Random, from its publication in 1748 to its second publication in 1792 and beyond.

Whiffle and Strutwell

One of the clearest ways Roderick Random engages with LGBT+ topics is in the books two confirmed gay characters, Captain Whiffle and Lord Strutwell. About a third of the way into the book, Roderick is working as a surgeon on a ship when their captain is replaced by Captain Whiffle. Whiffle is a wildly stereotypical gay man. The first paragraph about him is entirely devoted to his incredibly flamboyant appearance, including his pink and gold suit, his dark red pants, and the long ribbons hanging from his sword.²

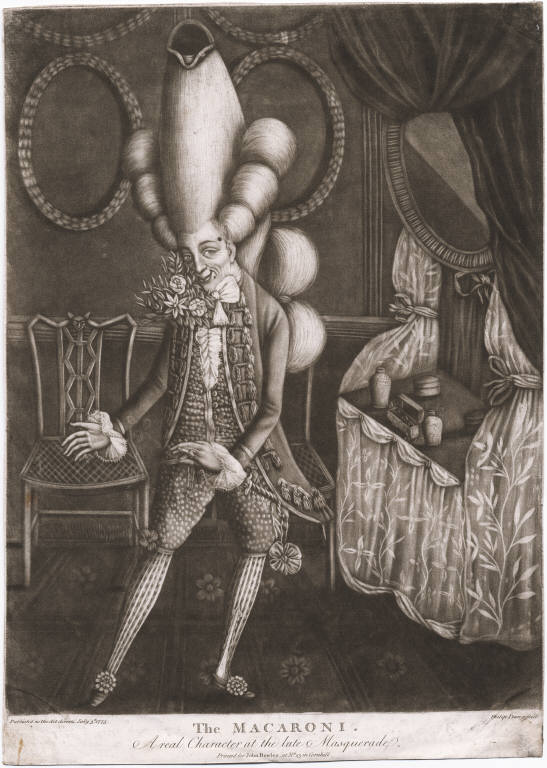

Any modern reader can see where this is going. To the eighteenth century reader, there were additional clues, such as Whiffle’s “meagre legs” which perfectly fit the popular stereotype of the day of homosexual males as the “spindle legged gentlman.”³

His over-the-top effeminacy is not, however, the most important part of Whiffle as LGBT+ representation. With his aggressively coded entrance into the story, it seems likely at first that Whiffle’s homosexuality is only going to be revealed through his adherence to stereotypes; this turns out not to be the case. Whiffle brings with him his own surgeon, a man named Simper (yes, Simper), and it quickly becomes clear that Simper is a special member of Whiffle’s entourage.Smollett then shows he is not afraid to directly state what he is getting at. After revealing that Whiffle has given Simper the bedroom attached to Whifffle’s own, and that there are rules in place to ensure no one walks in on them unexpectedly, Roderick tells the reader, “These singular regulations did not prepossess the ship’s company in his favour: but, on the contrary, gave scandal an opportunity to be very busy with his character, and accuse him of maintaining a correspondence with his surgeon not fit to be named.”⁴

Any eighteenth century reader would have known exactly what “a correspondence…not fit to be named,” meant. “Correspondence” in this context means interaction or relationship. Throughout the eighteenth century phrases like “a crime not fit to be named” and variations thereof were a very common euphemism for same-sex intercourse.⁵ I was astonished at how directly Smollett addresses homosexuality here. I had assumed that, in an era so ostensibly homophobic, a writer would not do more than allude to a character’s LGBT+ identity. As it turned out, I was wrong.

Later in the book, Roderick finds himself out of luck and out of money, and turns to an acquaintance with high connections. This aqaintance suggests he may be able to help Roderick by introducing him to Lord Strutwell, the book’s second confirmed gay character.⁶ Significantly, Strutwell does not fit the same stereotypes that Whiffle does.

When Roderick is introduced to Strutwell at one of the lord’s levees, Sturtwell is instantly impressed with him, and he eventually invites Roderick to visit him regularly at his home. Roderick does so, thrilled to seemingly be making so much progress towards gaining the assistance of an influential man. Roderick is so excited that he decides to overlook several displays of affection from Strutwell that go beyond what Roderick expects, such as when Strutwell rewards Rodericks gratitude by hugging and kissing him. This is intended by Smollett to be a comedic part of the book, as he assumes the worldly reader will be amused by Roderick’s total ignorance of Strutwell’s obvious intentions.⁷

One of the most interesting parts of this story arc is that the reader gets to see Strutwell actually give a defense of homosexuality. Hoping to sound out Roderick’s receptiveness to his advances, Strutwell asks Roderick’s opinion of an ancient author known apparently by both to be homosexual. Roderick expresses disgust, to which Strutwell replies:

“I own…that his taste in love is generally decried, and indeed condemned by our laws; but perhaps that may be more owing to prejudice and misapprehension than to true reason and deliberation. The best man among the ancients is said to have entertained that passion; one of the wisest of their legislators has permitted the indulgence of it in his commonwealth; the most celebrated poets have not scrupled to avow it…Indeed there is something to be said in vindication of it; for, notwithstanding the severity of the law against offenders in this way, it must be confessed that the practice of this passion is unattended with that curse and burthen [sic] upon society which proceeds from a race of miserable and deserted bastards…it likewise prevents the debauchery of many a young maiden, and the prostitution of honest men’s wives; not to mention the consideration of health…”⁸

The chief reason this is included is to incite more comedy: Roderick still does not understand that Strutwell is gay, and thinks this is a test of his own morals, which he will fail if he is agrees with any of Strutwell’s arguments. Because of that, Roderick’s response (the recitation of a poem about how LGBT+ people are a plague on England) should not be taken completely seriously.⁹ But though readers may be intended to laugh at Roderick’s response, they are also intended to laugh at Strutwell’s arguments. Much satire of the day written to make fun of LGBT+ men included those men trying to defend themselves, often using precedents they claimed were set by Ancient Greece or Rome. Smollett assumed his readers would be amused by someone they viewed as a moral degenerate trying to defend his crimes using lofty, sophisticated arguments. Additionally, it has been suggested that Strutwell is based on a real person.¹⁰ If this is true, it reinforces the idea that Smollett intends Strutwell to be laughed at, since it would be out of place with the rest of the sarcastic, satirical tone of the book to suddenly throw in an actual defense of a real person.

As I mentioned before, Sturtwell does not fit the stereotypes that Whiffle does. This hints at the existence of more than one stereotype for gay men of that time. Strutwell is powerful, and uses his power to lure in young men whom he can then seduce. After he finally realizes Strutwell is gay, Roderick realizes that Strutwell’s servant does not like Roderick because until Roderick arrived this servant “had been the favourite pathic of his lord.”¹¹ A “pathic” refers to someone who plays the submissive role in sex.¹² Thus it is possible the two stereotypical images of gay men arranged themselves along these lines: the effeminate, weak passive, and the sinister, controlling active partner. Whether or not the stereotypes of the day did line up with sexual roles, it is important to note that an active male partner is being condemned for his actions, as some homophobic societies only (or at least more heavily) condem passive partners in male-male relationships because they are seen as going against gender roles.

“A Great Number of Gay Figures”

Though Whiffle and Strutwell are the only characters explicitly revealed to be gay, they may not be the book’s only gay characters. In the later half of the book, not long before being introduced to Strutwell, Roderick becomes part of a group of friends who are also described with some eighteenth century hints. Roderick has just made the acquaintance of a man named Medlar when suddenly they are interrupted by a man who is described as seeming silly and a bit theatrical. “This ridiculous oddity danced up to the table at which we sat,” Roderick tells the reader, “and, after a thousand grimaces, asked my friend by the name of Mr. Medlar, if we were not engaged upon business.”¹³ During this time period “grimaces” did not mean looks of disgust or discomfort, but more accurately over-done, grotesquely theatrical expressions. Interestingly, Smollett uses this word often throughout the book for similar characters. By describing this man (who turns out to be named Dr. Wagtail) as a “ridiculous oddity” and his movements as “dancing” Smollett may be trying to imply Wagtail is gay. This only continues when Roderick goes with Wagtail to meet this man’s other friends, who are immediately described as “a great number of gay figures fluttering about.”¹⁴ Though gay did not have the meaning then that it does now, it meant something like happy-go-lucky, and was often used in that way to refer derisively to homosexual men.

Despite the implications that these men might be LGBT+, Smollett does not disrespect them to the same extent he does Whiffle and Strutwell. Perhaps these men are meant to show a middle ground between the two; they are not as weak and unmasculine as Whiffle, nor are they dangerous and untrustworthy like Strutwell. Instead Smollet views them as a third, harmless type of LGBT+ man, one whom Roderick can risk being around, even if they are not quite the caliber of man he would prefer to spend time with.

Why does all this matter?

There are many possible takeaways from analyzing the LGBT+ representation in The Adventures of Roderick Random: the pair of stereotypes displayed by Whiffle and Strutwell, the specific terminology used, and the hints Smollett knew his audience would understand. The most important takeaway from Roderick Random’s LGBT+ representation, however, is bigger than any of these things.

In George Chauncey’s book Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World 1890-1940, Chauncey describes three common myths about LGBT+ history, one of which is the “Myth of Invisiblity.” The “Myth of Invisiblity” is the myth that in homophobic societies, if an LGBT+ subculture existed, it was completely invisible to the outside world.¹⁵ There is a widespread belief that cis-het people in the eighteenth century United States had no idea LGBT+ people even existed; Roderick Random proves this is not true. The cis-het world of eighteenth-century America was equipped with stereotypes, slang, and a variety of crude jokes with which to discuss LGBT+ people. Far from being unknown to cis-het Americans, LGBT+ people were amusing and even intriguing to them.

Chauncey’s other myth that is relevant here is the “Myth of Isolation.” This myth holds that in homophobic societies of the past there was no LGBT+ subculture at all. A gay man, for example (because that is all the LGBT+ representation Random really has) might know that he was gay, but he would think he was the only one.¹⁶ Roderick Random disproves this myth too. For one thing, it would not make sense that the dominant, cis-het culture was aware there were lots of LGBT+ people while LGBT+ people themselves were not. For another thing, this book itself may have made some gay men realize there were others like them. Even though Smollett is derogatory, he not only proves that he is aware of gay men, but shows through his use of gay men in comedy that he expects most if not all of his audience to be familiar with the concept as well. By reading Roderick Random, a gay man would have seen that not only was he not the only gay man in the world, but that homosexuality was widespread, to the point where mainstream entertainment was discussing it.

Reading The Adventures of Roderick Random was an eye-opening experience for me. Though I thought I had long ago left behind the belief that in the eighteenth century no one talked about or understood LGBT+ things, I was shocked to see how openly it was discussed. In order to properly study LGBT+ history, we must all leave behind the inaccurate pictures of mid-to-late eighteenth century America that tell us that homosexuality was completely kept in the dark, only known to individual LGBT+ people who knew only of their own experience. Only when we approach this time with a mind devoid of preconceptions can we grasp its unique and nuanced character, and begin to really see through the eyes of eighteenth century Americans, cis-het and LGBT+.

If you enjoy my work, please consider becoming my Patron! 18th Century Pride is creating LGBT+ History Content | Patreon

- “Mapping an Atlantic Sexual Culture: Homoeroticism in Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia”, Clare A. Lyons

- The Adventures of Roderick Random, T. Smollet, 162

- Rictor Norton (Ed.), “Sir Narcissus Foplin, 1708”, Homosexuality in Eighteenth-Century England: A Sourcebook, 14 May 2010 <http://rictornorton.co.uk/eighteen/foplin.htm>.

- The Adventures of Roderick Random, T. Smollet, 165-166

- ““Not fit to be mentioned”: Eighteenth-Century Sodomy and Francis Lathom’s The Midnight Bell”, Christine Mangan, http://studiesingothicfiction.weebly.com/uploads/2/2/8/8/22885250/sgf5.1_final.pdf

- The Adventures of Roderick Random, T. Smollet, 165

- Ibid., 256

- Ibid., 257-258

- Ibid., 258

- Rictor Norton (Ed.), “Lord Strutwell, 1748”, Homosexuality in Eighteenth-Century England: A Sourcebook, 22 February 2003 <http://rictornorton.co.uk/eighteen/strutwel.htm>.

- The Adventures of Roderick Random, T. Smollet, 260

- “Pathic”, https://www.thefreedictionary.com/pathic

- The Adventures of Roderick Random, T. Smollet, 221

- Ibid., 224

- Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World 1890-1940, George Chauncey, 3

- Ibid., 2