France’s Transgender Superspy

Quite a lot has been written about the Chevalier d’Eon. Her skills as a writer, spy, diplomat and soldier landed her at the center of some of the most important historical events of her age. She also has the distinction of having been eccentric and arrogant enough to blackmail two kings of France – and get away with it. Another facet of her life that has been the subject of much debate is her gender. Despite being assigned male at birth, d’Eon spent the last thirty years of her life living as a woman. Many historians have tried to claim she was forced to do this, or did it out of necessity. But much of the evidence from d’Eon’s life suggests a much simpler explanation: the Chevalier d’Eon was a transgender woman.

The Chevalier(e) D’Eon

Charles-Geneviève-Louise-Auguste-André-Timothée d’Eon de Beaumont was born October 5th, 1728, in Tonnerre, France, to a family of minor nobles.¹ Eighty-one years later, when d’Eon was autopsied, the doctors would declare d’Eon to have “male organs of generation in every respect perfectly formed,” so d’Eon was most likely assigned male at birth.² D’Eon proved to be a bright and athletic young person. She attended college, where she studied civil and canon law, and then became a lawyer. When she was twenty-seven years old, d’Eon was recruited by King Louis XV to be part of his personal spy ring, “Le Secret du Roi”. In this capacity d’Eon was sent to Russia to open alliance talks with Empress Elizabeth I. Though historians debate the truth of this story, d’Eon later claimed she went to the Russian Court undercover, dressed as a woman. Either way, she secured an alliance and won the King’s favor. In the next few years d’Eon won renown as a soldier in the Seven Years’ War, helped negotiate the treaty that ended the war, and was appointed secretary to France’s ambassador to Britain.³

Eventually d’Eon was made temporary ambassador to Britain, but when the new permanent ambassador was announced, d’Eon refused to step aside. The new ambassador was Comte de Guechery, a man d’Eon had grown to despise while they had served together in the war. d’Eon would not step aside for a man she hated, especially when she was informed she was being demoted back to secretary, placing Guechery as her superior. Now there were two ambassadors fighting over one job. Guechery claimed d’Eon had slandered him in the press. D’Eon claimed Guechery had tried to poison her. A judge decided that both were telling the truth. D’Eon started stockpiling weapons and Guechery started hiring men to pretend to be ghosts haunting d’Eon’s house. Eventually, out of money and at her wits end, d’Eon wrote to the foreign minister that if the King did not make things right, she would publish the correspondence that proved France had planned to invade the same country with which they had just signed a treaty. Britain and France would almost certainly go to war. Louis XV replaced Guechery with an ambassador d’Eon liked and offered d’Eon money. The matter was settled for now, but as long as d’Eon had the secret papers, she was a threat.⁴

The Rumors

In 1770, a rumor began to spread across London that d’Eon was actually a woman in disguise as a man. Soon the whole city was arguing the matter, and in London’s coffee houses and bars bets began to be made about d’Eon’s genitalia.⁵

Knowing that d’Eon was actually born with a penis, it is rather confusing that the rumor that d’Eon was secretly a (cisgender) woman in disguise got started in the first place. In “Biographical Memoirs of the Late Chevalier D’Eon”, published in The Gentleman’s Magazine in 1810, it is alleged that “The Chevalier was engaged in two or three duels; and a wound received in one of these led to the suspicion of his sex [emphasis original].”⁶ Having been raised as a man in eighteenth century France, d’Eon was obsessed with honor culture, and so the idea that she was involved in several duels is quite likely. What injuries she would have received that made people think she had a vagina is unclear. The other available explanation is that d’Eon may have actually said to a person or people that she was a woman. Many people, of varying credibility, claimed d’Eon had told them she was a woman, or that they had heard her tell someone else.⁷ If any of these claims are true, they could be evidence that d’Eon was a transgender woman.

More and more people were caught up in speculation about d’Eon’s body. Cartoons began to be published making jokes about the Chevalier’s ambiguity, and the amount of money poured into bets on the matter soared.⁸ In 1777 this would lead to a court case in which two doctors and one of d’Eon’s friends would testify that d’Eon had allowed them to view and touch her genitals. The friend, Charles Morande, who will be discussed later, also alleged that d’Eon had shown him women’s clothing and jewelry that she had begun purchasing. Other sources agree that d’Eon had indeed begun buying women’s clothing.⁹ All of the testimony about d’Eon’s genitals, of course, we know to be lies, since it all centered on knowledge of genitals d’Eon’s autopsy would later reveal she did not have. Still, that could hardly have made the experience less disturbing for d’Eon. Even before the court case, d’Eon was aware that many people had sunk small fortunes into the question of what she looked like naked. D’Eon must have feared that she would be kidnapped or killed for the purpose of stripping her naked and settling the question once and for all.

The experience must have been doubly upsetting if d’Eon was indeed a trans woman. As the question of d’Eon’s true sex was debated, d’Eon received constant reminders that her society believed it is having a vagina that makes one a woman.

Beaumarchais and the “Transaction”

In 1775, in the midst of the rumors and before the court case, Louis XVI sent Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, a bisexual playwright and business man, to seduce d’Eon into giving up the secret papers. Beaumarchais went to London, and in time allowed himself to be introduced naturally to d’Eon. D’Eon knew exactly why Beaumarchais was there, and was eager to begin negotiations. D’Eon was tired of living in notoriety, constantly in danger of being kidnapped or killed by agents of Geuchery or the King himself. She wanted to return home to France. When Beaumarchais made it clear he was going to play hard to get with the King’s favor, d’Eon apparently became emotional, and exclaimed “I am an unhappy woman!”¹⁰ This story comes to us from a letter Beaumarchais wrote to Louis XVI. This seems to be one of the most credible accounts we have of d’Eon telling someone she was a woman. After all, Beaumarchais had nothing to gain from d’Eon being female. All he needed was the papers back, and all Louis XVI wanted to hear was that Beaumarchais was making progress. It did not matter to either whether d’Eon was a man or a woman.

Accepting Beaumarchais’ story as true, some people still question d’Eon’s motives for telling him she was a woman. It has been suggested that d’Eon hoped that by convincing Beaumarchais (and therefore the King) that she was female, she could secure money and mercy. It is true that in the final negotiations, d’Eon was granted a pension; but would she not have demanded a pension for her military and governmental services, even negotiating as a man? And would Louis XVI, desperate to see the destruction of papers that could force France into a war for which it was completely unprepared, have been less willing to give a large sum of money to a man? Then there’s the question of mercy. This is the theory that d’Eon claimed to be a woman in order to get the King to stop sending assassins and kidnappers, and perhaps to get Beaumarchais to be much gentler in his negotiations. D’Eon’s admission may have had this effect on the playwright: in a letter to Louis XVI, Beaumarchais gushed “when one thinks that this creature, so much persecuted, belongs to a sex to which one forgives everything, the heart is touched with a sweet compassion.”¹¹ Beaumarchais clearly regretted that the French government had been so hard on someone who all along was a woman. That this could have been d’Eon’s intention, however, seems remarkably out of character. To purposely use being a woman as a means to get sexist men to be more forgiving is to accept a role as a helpless, foolish woman, who needs to be protected and held sacred by men. Even once living as a woman, d’Eon was obsessed with honor. All her life she worked hard to be seen as fearsome and dignified. When she had been confronted with assassins and kidnappers previously, she had stockpiled weapons and sent threats to the King of France. That she would later debase herself in this way does not make sense, regardless of her true gender.

If d’Eon did not tell Beaumarchais she was a woman in order to get money or mercy, the most logical explanation is that she said it simply because it was true. Why she chose to tell him at that moment is somewhat unclear. Perhaps, emotionally exhausted from the life she had been living, and tired of being embroiled in conspiracies, she simply no longer wished to be burdened with this secret. In the aftermath of this emotional moment, d’Eon and Beaumarchais began to become close. Though it seems likely that Beaumarchais was still just charming d’Eon in order to manipulate her, d’Eon seems to have genuinely fallen in love with him. She wrote him many romantic letters, telling him in one that “My heart, which has been closed to other men, naturally opens in your presence, like a flower spreading itself out in a ray of sunshine.”¹²

As their strange relationship continued, Beaumarchais planned how he would negotiate with d’Eon for the secret papers. Beaumarchais frequently reported back to Louis XVI and to Comte de Vergennes, the French Foreign Minister. In the course of this correspondence it was agreed upon that if d’Eon was to return to France, she should do so as a woman.¹³ It is entirely possible that this started with d’Eon suggesting she might want to start presenting as a woman, prompting Louis XVI and his agents to see a utility in the idea. If d’Eon publicly declared herself to be a woman, she would be silenced permanently. In addition to having surrendered the papers, d’Eon would have surrendered the ability to tell anyone what they had said, because who was going to listen to a woman? It would also mean she could never claim to speak for the French Government again.¹⁴ And so, d’Eon beginning to live as a woman was made Article 4 of a contract which d’Eon and Beaumarchais called “the Transaction.”¹⁵

In the Transaction, Beaumarchais refers to a story d’Eon had apparently told him, and which she would retell publicly later. According to d’Eon, she had been born with a working vagina and uterus, but her parents had decided to pretend she was a boy in order to collect an inheritance her mother would only receive if she had a son.¹⁶ Because of this story, Beaumarchais says in the Transaction that the fault for d’Eon’s deception (pretending to be a man) “is entirely with their parents.”¹⁷ This story, odd enough on its own, becomes very strange when we consider that d’Eon’s autopsy would prove she was not born with a vagina and uterus as she claimed. There would have been no need to pretend d’Eon was a son; it would have been assumed the moment she was born. Perhaps d’Eon thought this story would be a good way to explain to the public why she had lived as a man if she was now claiming she was actually a woman.

D’Eon did not seem to have any objections to living as a woman, except that it meant the end of her career. In a part of the Transaction where d’Eon vowed to live as a woman, she vows: “I submit to all the conditions imposed above in the name of the king, only to give His Majesty the greatest proof possible of my respect and submission, although it would have been much sweeter if he had deigned to employ me again in his armies or in politics, according to my strong solicitations and according to my rank of seniority.”¹⁸ She reiterates this feeling later on, promising “to take back and wear my girlish clothes until death, unless in favor of the long habit I have been in of being dressed in my military dress…”¹⁹ This reveals a struggle d’Eon seems to have had throughout her life. Though she may have wanted to live as a woman, she knew that the moment she started to, her career as a soldier and diplomat would be over. D’Eon loved playing an important part in the success of her nation, and it was no doubt a heavy blow when she realized she would never play that part again.

Transformation

In October of 1777, d’Eon returned to France. The first thing she did was go to Versailles and meet with Vergennes. D’Eon was angry, for two reasons: first, she believed she should be allowed to continue wearing her uniform. As previously stated, d’Eon felt it was unfair that she had to give up life as a hardened soldier and powerful politician simply because she was preparing to begin life as a woman. She was also mad about the conduct of Beaumarchais. Beaumachais’ friend Charles Morande had revealed to d’Eon that he and the playwright had gambled a small fortune on the question of d’Eon’s sex. D’Eon was outraged that the man she had fallen in love with could have become part of the public harassment she faced, and she was now angry at the French Government for making her deal with such crass and unfeeling men. Most of her problems fell on deaf ears, but Vergennes did offer a way to smooth things over: the government would help her with her transformation.²⁰

Louis XVI agreed to pay for d’Eon’s entire new wardrobe, and Marie Antoinette called in her personal dressmaker, Rose Bertin. D’Eon ordered corsets and wigs from the most elite designers in France. Over the next few weeks, d’Eon underwent a complete makeover. When d’Eon was formally introduced to the King and Queen, she wore an ornate dress, a three tiered wig, and her hands had been treated to make them soft and delicate.²¹ D’Eon said of the experience “All I know is that my transformation has made me into a new creature!”²² Much of this story seems to support the theory that d’Eon had said she wanted to live as a woman, and the Court was just going along with it; if presenting as female was something Louis XVI was forcing on d’Eon, paying for the process would hardly have seemed like a conciliatory gesture. In exchange for giving up the papers and her ability to criticize the Crown, d’Eon was given a transgender fairy tale.

Later Life and Exposure

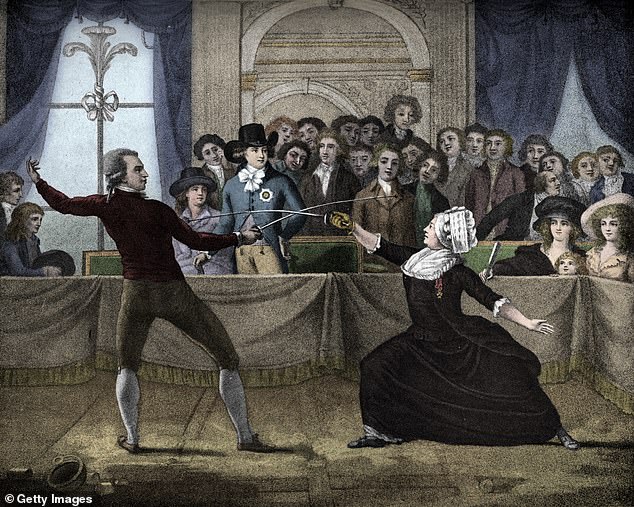

D’Eon’s stunning transformation was a sensation in France and probably also in England.²³ D’Eon, however, was still unsatisfied with what life as a woman was going to entail for her. She later asked the King to grant her a military command, but of course now that she was seen as a woman the idea was unthinkable, even though she was a decorated veteran.²⁴ D’Eon had to find a new career, and so she spent many years tutoring young gentlemen in the art of fencing. Her sword fighting skills were so impressive that she was invited to be part of competitions and performances, and she gained some renown as a fencer.²⁵ After sustaining a serious wound, d’Eon retired to a quiet life as a seamstress. A few years later, having been in bad health for some time, Chevalier d’Eon died on the 21st of May, 1810.²⁶

The story of d’Eon’s posthumous exposure is one that will sound very familiar to any student of LGBT+ history. After d’Eon’s death, her friend and roommate Mary Cole set about preparing d’Eon for burial. When she undressed her friend, she did not find the body she had been expecting. Cole called in the doctor/priest who had been attending d’Eon, and then either he or Cole called several more doctors. D’Eon’s body was examined repeatedly, and then unnecessarily autopsied.²⁷ Thomas Copeland, a surgeon, declared “I hereby certify that I inspected and dissected the body of le Chevalier d’Eon…and found the male organs of generation in every respect perfectly formed.”²⁸ Copeland’s comment about d’Eon’s sex organs being “perfectly formed” was not just flowery prose. In the language of the day, Copeland meant that d’Eon was not intersex. While intersex conditions were not well understood at the time, they were something doctors were aware of, and the idea that a person’s body might not always conform to the expectations of male or female was part of the popular imagination. Indeed, when d’Eon’s true sex was speculated about by the general public, the idea that d’Eon was intersex (they would have said “a hermaphrodite”) was always suggested.

Chevalier d’Eon is an interesting person for so many reasons, and her gender is another thread in the tapestry of her fascinating life. D’Eon’s autopsy proved she had the sex organs her society would have expected a man to have, and so she must have been assigned male at birth; and yet, she spent the last thirty years of her life living as a woman. It has often been alleged that d’Eon lied about being a woman to secure money and mercy, but she would have received money either way, and neither d’Eon the sharp witted diplomat nor d’Eon hardened veteran of the Seven Years’ War was about to beg for mercy. It has also been alleged that Louis XVI and his agents forced d’Eon to live as a woman against the Chevalier’s will, but while Louis XVI stood to gain if d’Eon lived publicly as a woman, he also seemed to treat helping d’Eon transition as a benefit she got from handing over the secret papers. This leaves us with the most logical conclusion being that d’Eon was a transgender woman. And though she may not always have gotten the respect she deserved in life, we can show her respect now by acknowledging her as the arrogant, eccentric, brilliant, and courageous transgender woman she always was.

If you feel oyu have learned something from my work, please consider becoming my Patron! 18th Century Pride is creating LGBT+ History Content | Patreon

- Unlikely Allies, Joel Richard Paul, 33

- “Certificate of Thomas Copeland, Surgeon”, quoted in Unlikely Allies, Joel Richard Paul, 342

- Paul, 33-40

- Paul, 45-50

- Paul, 45

- “Biographical Memoirs of the Late Chevalier d’Eon”, The Gentleman’s Magazine, Biographical Memoirs of the Late Chevalier D’Eon – Digital Transgender Archive

- See #9 and Paul, 51

- Paul, 51

- For the court case, see: “Memoirs of the Chevalier d’Eon”, The Town and Country Magazine, Memoirs of the Chevalier D’Eon – Digital Transgender Archive; for d’Eon purchasing women’s clothes prior to the Transaction: Paul, 89

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 87

- Ibid, 93

- Ibid., 88

- Ibid.

- “Transaction”, quoted in Mémoires sur la Chevalier d’Eon, Frederic Gaillardet, 238, Mémoires sur la chevalière d’Eon la vérité sur les mystères de sa vie, d’après des documents authentiques ; suivis de Douze lettres inédites de Beaumarchais / par Frédéric Gaillardet : Gaillardet, Frédéric (1808-1882) : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

- Paul, 85-86

- See #15

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Paul, 262

- Ibid., 264

- Ibid., 263

- Ibid., 264

- See #6

- Paul, 340

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- See #2