18thc. LGBT+ Terms for Females

At the start of my research into LGBTQIA+ women of the Revolutionary and Founding Eras, I was told that at that time LGBTQIA+ women, as a concept, did not exist. The people who espoused this theory were not trying to say LGBTQIA+ women actually did not exist back then; obviously LGBTQIA+ women have existed as long as humanity. That being said, at some points in the eighteenth century there was a minsconception that all sex had to involve a penis, and some researchers have inferred from this that people in the eighteenth century would never have imagined that women could have relationships with other women. There are a few problems with this theory: for one thing, it is problematic because it overlooks non-sexual dimensions of a romantic relationship, and thus fails to answer the question of whether people from this era thought women could fall in love with each other. Beyond that, this way of looking at the eighteenth century is not accurate. It is true that this belief existed at the time, and this misconception did lead to erasure of LGBTQIA+ women just as there are misconceptions that erase LGBTQIA+ women today. The problem with just focusing on this misconception is that it paints a picture of an eighteenth century that really had no idea that LGBTQIA+ women existed; one which did not think about LGBTQIA+ women, did not talk about LGBTQIA+ women, and did not offer LGBTQIA+ women themselves any sort of framework for understanding who they were. My results of my investigation into four eighteenth century terms -sapphic, lesbian, tribade, and tommy -tell a very different story.

Sapphic (or Sapphick) Love and Lesbians

The term sapphic (sometimes spelled in documents from the time as “sapphick”) came from the Greek poet Sappho. Born in 610 BCE, Sappho was a brilliant poet who charmed audiences through her blend of traditional style and vibrant personality.⁶ Many of Sappho’s poems were love poems written to other women, and many eras have looked back at her as something like a metaphorical ancient ancestor of all LGBTQIA+ women, particularly lesbians. In England, sapphic/sapphick love was a common descriptor for romantic and/or sexual love that happened between women. One satirical poem, intended to shame an actress named Kitty Clive whom the writer believed to be a lesbian, included the lines “While Strawberry-hill at once doth prove, / Taste, elegance, and Sapphick love, / In gentle Kitty *****[i.e. Clive].”⁷ Similarly, an English man travelling through Portugal remarked “Sapphic love rises predominant here; the stories I have heard of the females, who indulge themselves in this passion, are almost incredible.”⁸

Sappho and sapphic/sapphick came up frequently in my searches of eighteenth century American documents, such as when François Adriaan Van der Kemp mentioned to John Adams “Apollo with the nine—or ten muses—if Sappho may be included.”⁹ In another instance, John Quincey Adams commented in his diary: “And of all the kinds of verse, that are used by this Poet the Sapphic, I think has the most dignity.”¹⁰ Obviously neither of these uses has any sort of LGBT+ implication; the first one is a reference to Sappho as a great poet, and the second is a reference to Sapphic Stanza, a type of poetic stanza that Sappho invented. What these quotes do show however is that Sappho was very much a part of American culture, at least amongst the educated. Sappho was on the American mind, and since it was common knowledge in England that Sappho was homosexual, it would make sense that this fact was not attached to her name in America. Therefore an eighteenth century American looking for a word to describe romantic and/or sexual love between women would likely have thought to call it “sapphic love” or otherwise to describe the relationship or the women as sapphic, or as being like Sappho.

Lesbian

The term “lesbian” did not mean exactly what it does today, but it was beginning its evolution. Lesbos is the island where Sappho lived, and a person from Lesbos is referred to (even to this day) as a Lesbian. Lesbos became very closely associated with Sappho in Euroamerican culture, and because of this the word comes up a lot in popular discussion of LGBTQIA+ women at the time. A prime example of this is when a surgeon writing about a homosexual woman described her as “far from being inferior to Sappho, or any of the Lesbian Nymphs, in an Attachment for those of her own Sex.”¹¹ (emphasis original) If someone in the eighteenth century was trying to say a woman was attracted to other women, they would not say she was a lesbian; they would, however, compare her to women from Lesbos, or Lesbians.If the word “sapphic” as an adjective for female-female love did make it to America, Lesbian certainly would have come with it.This is interesting because it means that if someone from present day traveled back in time to the Revolutionary or Founding Era and told one of our founding fathers that a woman was a lesbian, the founding father would probably be able to piece together what they meant. The founder would understand this as just being a shorter way to say “she’s like a woman from Lesbos”, which, in a way, is exactly what we are doing when we use this word.

Tribade

The term tribade comes from the Greek word tribas, which means to rub, and as one can imagine it was attached to LGBTQIA+ women as a crude sexual reference.⁴ This is noteworthy for two reasons: it shows that people of the time often had a narrow image of how women had sex together, and it shows that female-female realtions were seen as exclusively sexual and vulgar.

When I first started researching eighteenth century LGBT+ people I heard historians use the term “tribade” on a number of occasions. In my own research though I only found one use of the term, in an English translation of a French book from 1695.⁵ Logically speaking, all of these terms were probably used more than what surviving sources reflect; still, tribade does not seem to have ever been as popular as tommy or sapphic, and it is therefore doubtful that it made it to America.

Tommy

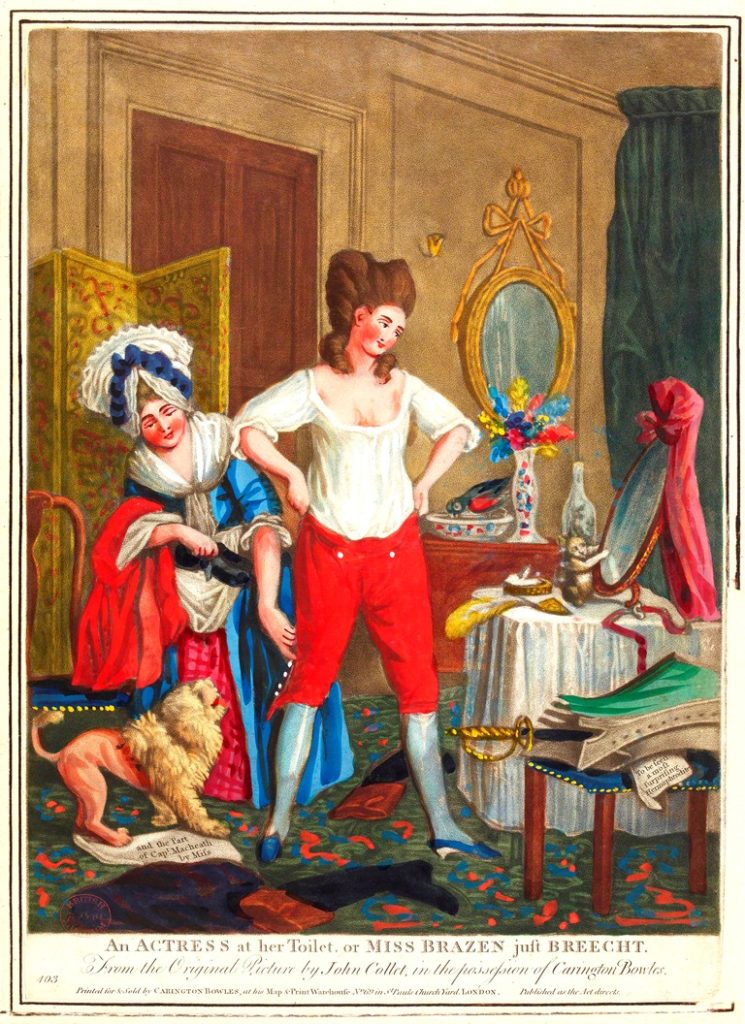

The word “tommy” appears to have been the female equivalent of “molly”, in that it was a casual term for someone attracted to people of the same sex. There may also have been the implication (again, parallel to the word molly) that a “tommy” was an unusually masculine woman.

When I studied the word molly for my last post, I at first thought it was not used in America because I only found one instance of it in the correspondence I was looking through, but I later found a written record from the time indicating that it was used in casual speech. This means that the absence of tommy from available Revolutionary and Founding Era correspondence does not necessarily mean people of the time did not use it in conversation. The question then is if tommy could have gotten to America like molly did. Molly came to America through the American consumption of literature and news from England. America watched as “molly houses” and molly subculture were revealed to the rest of English society, and saw molly used as a slang term for homosexual males countless times in offensive satire and discussions of England’s supposedly erroding morality. The word tommy may not have gotten the same amount of media attention. Sex between women was not illegal, so the word is absent from court records and from all true crime literature that reached America.¹ If there was a subculture of LGBTQIA+ women in eighteenth century England, it appears never to have been uncovered, depriving “tommy” of that media attention as well. Tommy did however get a decent amount of casual use in England. Just like molly, tommy was used in satirical poetry, such as one anonymously written piece called The Adulteress in which the poet remarks: “Woman with Woman act the Many Part, / And kiss and press each other to the heart. / Unnat’ral Crimes like these my Satire vex / I know a thousand Tommies ‘mongst the Sex.”² (emphasis original) Similarly, a poem entitled “A Sapphick Epistle” written to harrass a sculpter named Anne Damer, includes a footnote with the line “She was the first Tommy the world has upon record; but to do her justice, though there hath been many Tommies since, yet we never had but one Sappho.”³ There is currently a lack of available primary sources about LGBTQIA+ women in the eighteenth century, so it is hard to say for sure whether Americans would have used this term. Like with molly, it is possible that I was unable to find examples of it because it was not used often in writing and was only used in very casual speech. On the other hand, it is possible tommy did not enter American culture, because unlike molly it did not get the same amount of use in print media. The fact that relations between women were not illegal in England and no LGBTQIA+ female subculture was uncovered there at that time meant tommy was deprived of the two many uses that brought “molly” to American readers.

If a Revolutionary or Founding Era American was going to talk about two women being in a relationship, or even just the idea of romantic or sexual love between women, they would most likely have talked about “sapphic love” or the women being like Sappho or one of her “Lesbian nymphs.” It is possible they may also have referred to the women being “tommies” in the same way that LGBTQIA+ men would have been referred to as “mollies.” Knowing these terms is definitely interesting from a linguistic point of view, but we can learn more from this than just how Americans from this time talked.

When I first began studying women’s LGBT+ history, I was told that because people of the eighteenth century believed sex was impossible without one of the people involved having a penis, most Revolutionary or Founding Era Americans had no idea LGBTQIA+ women existed. As it turns out, this is not entirely true. It is true that in that era it was often said that women were physically incapable of having sex together. This thinking was the reason same-sex relations between women were often not against the law like they were for men, the logic being that women simply could not commit these crimes. It seems that this thinking was not all pervasive, however. For one thing, sometimes they were illegal. Thomas Jefferson designed a special punishment for LGBTQIA+ women in the revised criminal code he wrote for Virginia in 1779.¹² More importantly, people of any era often have a deeper, or just different, understanding of things than their legal system does. As the sources analyzed here have shown, even in England where relations between women were never illegal, the people were talking about “sapphic love”, “lesbian nymphs”, and spreading rumors about which women they thought might be loving other women. The difference between the eighteenth century I was picturing when I started this and the one that now emerges could not be more important. Revolutionary and Founding Era Americans knew LGBTQIA+ women existed. They thought about them. They talked about them. More than that, LGBTQIA+ women themselves had a way to understand what they were feeling. A woman who was starting to realize she was attracted to women might call herself a tommy and look to Sappho as a great woman who was like her. LGBTQIA+ women and those who wondered about them had a framework for understanding, and this fact opens up a dimension of Revolutionary and Founding Era America.

If you value my work, please consider becoming my Patron! 18th Century Pride is creating LGBT+ History Content | Patreon

- “Homosexuality”, https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/static/Gay.jsp

- Rictor Norton (ed.), “The Macaroni Club: The Adulteress, 1773”, Homosexuality in Eighteenth-Century England: A Sourcebook, 11 June 2005 <http://rictornorton.co.uk/eighteen/macaron8.htm>.

- Rictor Norton (Ed.), “A Sapphick Epistle, 1778”, Homosexuality in Eighteenth-Century England: A Sourcebook. 1 December 1999, updated 23 February 2003 <http://rictornorton.co.uk/eighteen/sapphick.htm>.

- “Origin of the Word Tribade”, https://www.dictionary.com/browse/tribade

- The Voyage of the Sieur Le Maire, to the Canary Islands, Cape-Verde, Senegal, and Gambia, Jacques-Joseph Le Marie, 561, https://www.wdl.org/en/item/638/view/1/561/#q=tribade

- “Sappho”, The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sappho-Greek-poet

- See #3

- Rictor Norton (Ed.), “Sapphic Love in Portugal, 1777,” Homosexuality in Eighteenth-Century England: A Sourcebook. 7 October 2008 <http://rictornorton.co.uk/eighteen/1777dalr.htm>.

- François Adriaan Van der Kemp to John Adams, 11 November 1814, https://www.founders.archives.gov/?q=sappho&s=1111311111&sa=&r=8&sr=

- The Diary of John Quincy Adams, “21st.”, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/03-01-02-0008-0001-0021

- Rictor Norton (Ed.), “The Case of Catherine Vizzani, 1755”, Homosexuality in Eighteenth-Century England: A Sourcebook, 1 December 2005 <http://rictornorton.co.uk/eighteen/vizzani.htm>.

- A Bill for Proportioning Crimes and Punishments in Cases Heretofore Capital, 18 June 1779, Thomas Jefferson, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-02-02-0132-0004-0064

Justyouraveragesapphic

Hiya! Just wanted to say I really love your articles! I appreciate all the effort you put into them and it really doesn’t go unnoticed. Though I don’t usually leave comments, I’ve been reading them for quite a while and absolutely love learning new things about queer history, it’s really fascinating. So thank you for all your hard work, keep it up! 🙂

megangack

I’m so glad that you’ve been enjoying my articles, and that you’re learning from them.

Thank you also for leaving this comment. I don’t get a lot of feedback on by work, and it’s hard to know if anyone actually notices it. It means a lot to me to know that someone appriciates all of the work I put into this.