18thc. LGBT+ Terms for Nonbinary People

Thus far I have covered how people in Revolutionary and Founding Era America would have talked about LGBT+ men and women. To do just these two, however, would be to leave out several significant groups of people, who shall in this article be referred to under the umbrella term “nonbinary.” Despite persistent misconceptions to the contrary, nonbinary people have been around as along as hummanity just like every other LGBT+ identity. It would be easy to assume that nonbinary people would have been thrown under one of the eighteenth century terms I have already discussed, since late eighteenth century people did not have a good understanding of nonbinary identities. This may have been true in many cases, but as usual, things are not quite that simple. Through evolving uses of the word “hermaphrodite”, discussions of the relationship between sex and gender, and debates over the need for a singular gender neutral pronoun, eighteenth century Americans were timidly beginning a journey to understanding.

Gender “Hermaphrodites”

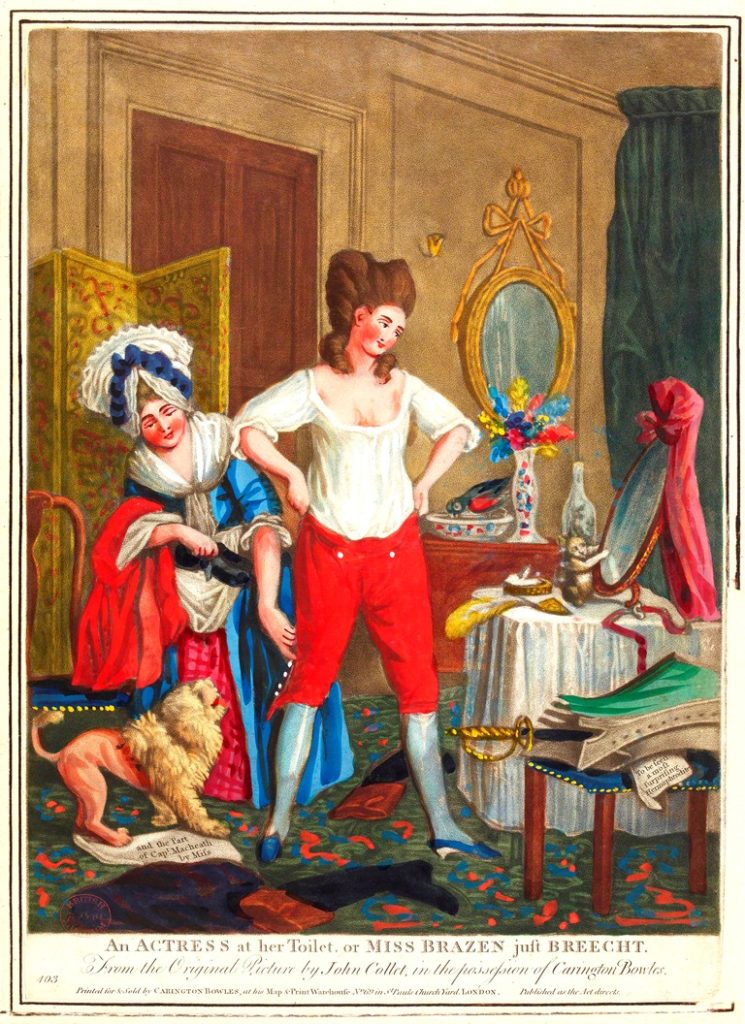

As discussed in my article on Casimir Pulaski, the term “hermaphrodite” in the eighteenth century refered, in the strictest medical sense, to an intersex person. In non-medical situations, however, the term was often used differently. For instance, James Callender, a poison tongue political journalist, described John Adams as “that hideous hermaphroditical character, which has neither the force and firmness of a man, nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman.”¹ By calling Adams “hermaphroditical” Callender was not trying to say Adams had indeterminate sex characteristics. Instead he was using the term in a more metaphorical sense, to say that Adams was not quite like a man or a woman. Though Callender was just trying to find a clever insult, his word choice still suggests that the term hermaphrodite (together with its variants hermaphroditic and hermaphroditical) was sometimes used to refer to someone who did not seem to be definetly masculine or feminine; therefore, it is likely that it would have been used for anyone who presented in a way different from how people of their biological sex were expected to, whether they were nonbinary or just gender transgressive.

On the other hand, some people of the time period actually did assume that all gender non-conforming people were intersex. This can be seen in a quote from Dr. Alexander Hamilton (no relation to the founding father). Dr. Hamilton wrote that he had observed a “carter driving his cart along the road, who seemed to be half man, half woman.” Though this person had a beard and was wearing a man’s shirt, they were also wearing a skirt and petticoats. Dr. Hamilton goes on to say that he wishes he could have “seen this creature turned topsy-turvy, to have known whether or not it was an hermaphrodite.”²

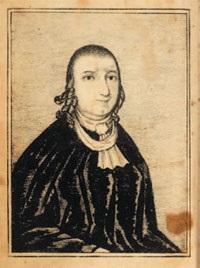

David Hudson

The assumption that all nonbinary people are intersex can also be seen in the public reaction to the individual known as The Public Universal Friend. The Friend was assigned female at birth, and lived as a woman for twenty-four years. Then, in 1776, The Friend became seriously ill. Upon recovering, The Friend insisted that the woman who had previously inhabited that body had gone on to Heaven, and the body had been taken over by the Holy Spirit. It was then that The Friend began using the name “The Public Universal Friend” and variations thereof. The Friend declared that as a body possessed by the Holy Spirit, The Friend could no longer be referred to as a woman, nor was The Friend a man. I do not use they/them for The Friend because The Friend did not seem to like any pronouns, as The Friend was supposedly no longer a person at all, but a divine being. As historian Scott Larson noted in his journal article “Indescribable Being”: Theological Performances of Genderlessness in the Society of the Publick Universal Friend, 1776–1819”, the claim that The Friend was neither man nor woman was integral to The Friend’s claim of divinity; thus, many people seeking to discredit The Friend did so by attempting to prove that The Friend was in fact a woman. One crude satire tried to do this by claiming that The Friend had gotten pregnant by a follower. While this piece was just a mean joke at The Friend’s follower’s expense, it shows that for people of the time, proof that The Friend had fully functioning female sex organs would be considered proof that The Friend could not truly be called genderless.³ For a person to be between male and female in identity and presentation, they believed, they must also be so in biology. This idea that all nonbinary people were intersex is of course closely related to another widly held misconception, then and now, that biological sex determines a person’s gender.

Sex vs. Gender

Unsurprisingly, people of the late eighteenth century believed that sex and gender are the same thing. In an essay on how to teach the English language, Thomas Jefferson proclaimed: “The word gender is, in nature, synonimous with Sex.”⁴ This seems to have been the general understanding at the time, as the word “sex” was used in situations where “gender” would be used today.

The only situation in which gender was seen as distinct from sex was in language. In some languages, namely French, all nouns are given a “gender”. For instance la main (the hand) is a feminine noun, whereas le chat (the cat) is masculine. Abigail Adams observed the function of gender in language when she responded to a cousin who was inquiring about an error someone seemed to have made in their French. The abbess of a nunnery had apparently referred to herself as “Serviteur,” the masculine form of the French word for servant. Adams explained to her cousin, “How the Lady abbess came to subscribe herself Serviteur, which you know is of the masculine Gender I cannot devise unless like all other Ladies in a convent, she chose to make use of the Masculine Gender, rather than the Feminine.”⁵ I am not entirely sure why nuns at the time would have used masculine French to refer to themselves, if this is indeed true. At any rate, in this instance we see Adams distinguishing between what she saw as the nun’s true sex (she still calls them “ladies”) and the linguistic gender they were using (“the masculine gender”). Jefferson saw this difference too. In the same essay in which Jefferson declared that sex and gender are synonimous “in nature,” he acknowledged that in French (and other languages like it) they were not synonymous. Jefferson explains how these languages assign gender to inanimate objects, and goes on to say that “some Latin grammarians have so far lost sight of the real and natural genders as to ascribe to that language 7 genders.”⁶ Thus late eighteenth century Americans could conceive of sex as separate from gender in languages that applied gender to all nouns, but still maintained that in the natural world sex and gender were the same thing.

Pronouns

According to Thomas Jefferson, among the genders that grammarians had made up, and which had no basis in nature, was that “which grammarians call Neutral, that is to say, of no gender or sex.”⁷ Though Jefferson was referring specifically to applying gender to nouns, his dismissal of gender neutral language is reflective of a debate that was in full swing at the time. Though the struggle for a gender neutral pronoun is often thought of as modern, it is anything but new. For centuries prior, “they/them” was acceptable as not just a plural pronoun, but also a singular gender neutral one. This did not mean someone could ask people to refer to them using they/them, but it did mean they/them was the default in sentences like “Someone left his book here.” Then in 1745, a British schoolmaster named Anne Fisher published a book called A New Grammar. In this book Fisher argued that “they” as a singular pronoun was technically incorrect, and that if someone does not know the gender of the person to whom they are referring, they are supposed to default to he/him/his. Fisher’s book was incredibly popular, and her advice caught on. As the eighteenth century progressed, most people began using he/him/his as a default.⁸

Not everyone was happy with this, however. Scottish economist James Anderson believed brand new pronouns needed to be invented to fill this need; Anderson’s proposed system actually had thirteen total pronouns, including the originals. Among these, Anderson put forth a new singular gender neutral pronoun, “ou.”⁹ Anderson’s suggestions never caught on, but he was not alone in recognizing that defaulting to he/him/his was not working. A particularly memorable example of this came in a debate between an all-women literary group called the Belle Assembly and a male author called Don Alonzo. In a series of back and forth essays with Alonzo, the Belle Assembly at one point used “they” in order to tell a story without initially revealing the gender of the person they were talking about. In his reply, Alonzo pointed out to the Assembly that this was grammatically incorrect. In their next piece the Assembly replied “With regard to our using the plural pronoun “them” in conjunction with the definitive pronoun “one,” as we wished to conceal the gender, we would ask the Don to coin us a substitute.” (emphasis original)¹⁰

It is interesting to consider that the fight for a singular gender neutral pronoun was already in process in the eighteenth century. It should be noted, however, that this war was not being waged on behalf of nonbinary people. Many of the people involved, including some for and some against the use of singular “them”, fought for grammar’s sake; these grammarians were thinking about what pronoun was correct in sentences like my earlier example “someone left his book here.” Others, as the quote from the Belle Assembly shows, recognized the implications of the situation for women. When it came to people who identified and/or presented as both or neither gender, however, people could be far less accommodating. Those who were not followers of The Universal Public Friend, for instance, continued to refer to The Friend using The Friend’s birth name along with she/her pronouns.¹¹ The Friend is a somewhat extreme example, given The Friend’s unique circumstance and the fact that validating The Friend’s gender identity was seen as validating The Friend’s theological claims. A better example perhaps is Dr. Hamilton’s description of the androgynous carter. When Dr. Hamilton begins his story about the cart driver he saw, Dr. Hamilton refers to the person as “driving his cart along the road” (emphasis added). Once he has revealed to his audience that this carter is of uncertain gender however, Dr. Hamilton uses “this creature,” and “it”.¹² Thus even amid debates about gender neutral words, no room was being made in language for people outside the binary.

I ended the other two articles in this series on terms ( for men and for women) by sharing the revelation that LGBT+ men and LGBT+ women were, contrary to what I had originally thought, concepts being actively discussed in Revolutionary and Founding Era America. The same cannot be said of nonbinary people. Late eighteenth century America was deeply buried in the idea that sex determines gender, something which collided with the era’s fascination with intersex people and led to the idea that a person could only be nonbinary if they were also intersex. Thus no place in language was created for nonbinary people: gender neutral pronouns, which many people did not see the need for, never got off the ground. When a person of uncertain gender was referred to, it was either by the pronouns that went with their biological sex, or it was with dehumanizing words like “it”.

On the other hand, it also cannot be said that people of that time had no concept of nonbinary people. Recall, for instance, that not everyone describing androgonous people as “hermaphrodites” was actually confusing nonbinary and intersex. Hermaphrodite was becoming a slang term; it still meant not quite male, not quite female, but in more of a casual sense than a medical one. In this usage of the word, eighteenth century Americans had a means to begin developing their understanding of other ways in which a person may not fit the male/female binary. The understanding of nonbinary people may have been in an embyronic stage, but as early as the eighteenth century, it was growing.

If you appriciate the work I do here, please consider becoming my Patron! 18th Century Pride is creating LGBT+ History Content | Patreon

- “Hideous Hermaphroditical Character”, Anna Berkes, https://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/hideous-hermaphroditical-character-spurious-quotation

- “”Indescribable Being”: Theological Performances of Genderlessness in the Society of the Publick Universal Friend, 1776–1819”, Scott Larson, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24474871?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

- Ibid.

- “An Essay or Introductory Lecture…Dialects of the English Language”, Thomas Jefferson, https://www.founders.archives.gov/?q=%22male%20or%20female%22&s=1111311111&sa=&r=16&sr=

- Abigail Smith to Isaac Smith Jr., 16 March 1763, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-01-02-0005

- See #4

- Ibid.

- “All-Purpose Pronoun”, Patricia T. O’Connor, Stewart Kellerman, https://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/26/magazine/26FOB-onlanguage-t.html

- “Pronoun Showdown (2017 Edition)”, Dr. Dennis Baron, http://faculty.las.illinois.edu/debaron/essays/Whats_your_pronoun_2017.pdf

- “Milcellany”, Charlotte Lisper, Lavina Prattle, Parthenia Trippett, http://faculty.las.illinois.edu/debaron/essays/new_pronoun_1794.pdf

- See #2